Source: Smart investors.

In this year's increasingly difficult market environment, Howard Marks' memos have been more frequent than last year.

On August 22nd, inspired by the global market turmoil in the first week of August, he wrote an article called 'Mr. Market Miscalculates'.

From this title, we should know his view on this matter.

From this title, we should know his view on this matter.

Howard took us back to revisit Graham's precise description of the behavior of 'Mr. Market' from years ago. This profound understanding and high-level summary from 75 years ago are fully applicable today, because 'the market is not built on natural laws, but on the unpredictable nature of investor psychology'.

And the ever-present flaws such as volatile psychology, distorted perception, excessive reaction, cognitive dissonance, rapid spread, irrationality, wishful thinking, forgetfulness, and lack of reliable principles...

Howard says that the best way to deal with the inevitable fluctuations in the market is to see through the 'Mr. Market's' excessive reactions and adapt to him. 'Sell to him when he is eager to buy, regardless of the price; buy from him when he urgently wants to exit.'

This is a memo with many memorable quotes, and Howard shares his collection of hidden-market comics, which is also very interesting.

As a teacher of Warren Buffett at Columbia Business School, the famous Benjamin Graham introduced a person he called the 'Mr. Market' in his book 'The Intelligent Investor' published for the first time in 1949:

Suppose you have a small (1000 dollars) amount of shares in a non-listed company. Your partner, who is called 'Mr. Market', is indeed a very enthusiastic person. Every day, he tells you the value of your equity based on his judgment, and he also asks you to sell all of your shares to him at this value or buy more shares from him.

Sometimes, his estimation seems to match the development and prospects of the company that you know; on the other hand, in many cases, the enthusiasm or worry of Mr. Market seems a bit excessive, so the value he estimated seems a bit foolish to you.

Of course, Graham meant to use 'Mr. Market' as a metaphor for the entire market.

Given the contradictory behavior of 'Mr. Market', the price he sets for the stocks every day may deviate significantly from the fair value, sometimes even far away. When he is overly enthusiastic, you can sell to him at an inflated price. And when he is overly fearful, you can buy from him at a price much lower than the underlying value.

Therefore, his mistakes provide profitable opportunities for investors interested in exploiting market misjudgments.

There is a lot to say about the weaknesses of investors, and I have shared a lot over the years.

However, the rapid decline and rebound in the market that we saw in the first week of August prompted me to summarize the comments that have been made about this topic and the priceless investment cartoons that have been collected, and add some new observations.

First, let's review recent events.

2022 was the worst year for stock and bond portfolios due to the COVID-19 pandemic, soaring inflation, and rapid rate hikes by the Federal Reserve. Investor sentiment hit its lowest point in the mid-2022 as people felt discouraged by the widespread pessimistic outlook: 'We are facing inflation, which is terrible. And raising interest rates in response to inflation will certainly lead to an economic recession, which is also terrible.'

Investors could hardly think of any positive factors.

Subsequently, the sentiment gradually eased.

By the end of 2022, investors began discussing a positive narrative: slow economic growth would lead to a decrease in inflation, allowing the Federal Reserve to start lowering interest rates in 2023, resulting in economic vitality and market returns.

The stock market started to rise sharply and continued almost uninterrupted until this month.

Despite the anticipated interest rate cuts in 2022 and 2023 not yet materializing, the optimistic sentiment in the stock market has been rising.

As of July 31, 2024, within 21 months, the S&P 500 stock index has risen by 54% (excluding dividends). On that day, Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell confirmed that the Fed is moving towards rate cuts, and the situation of economic growth and further appreciation of the stock market seems to be improving.

But on the same day, the Bank of Japan announced the largest increase in short-term interest rates in 17 years (up to 0.25%). This shocked the Japanese stock market, and people's enthusiasm for the Japanese stock market has been going on for over a year!

More importantly, this has had a serious impact on investors engaged in yen carry trade.

For many years, Japan's extremely low (often negative) interest rates have meant that people can borrow at low prices in Japan and invest the borrowed funds in any amount of assets, whether in Japan or elsewhere. These assets promise higher returns, thus obtaining a "positive carry" (also known as "free funds").

As a result, many funds have established highly leveraged positions. A quarter-percentage-point increase in interest rates requires the liquidation of some of these positions. This may seem strange, but it is indeed the case. As carry trade participants begin to reduce leverage, various asset classes experience positive sell-offs.

Starting from the next day, economic news announced by the United States is mixed with both positive and negative aspects.

On August 1st, we learned that the manufacturing purchasing managers' index had dropped and the number of initial jobless claims had increased. On the other hand, corporate profit margins continue to remain strong and productivity growth is unexpectedly high.

A day later, we learned that job growth had slowed down and the increase in the number of hirings was lower than expected. The unemployment rate at the end of July was 4.3%, higher than the low point of 3.4% in April 2023.

According to historical standards, this is still very low, but according to the suddenly popular "Sam rule" (don't complain to me, I haven't heard of it either), since 1970, when the economy has not fallen into a recession, the three-month average unemployment rate has never risen by 0.5 percentage points or more from the low point of the previous 12 months.

Around the same time, Warren Buffett's Berkshire Hathaway announced that it had sold a large portion of its Apple holdings.

In short, this news brought a triple blow. The flip from optimism to pessimism triggered a sharp drop in the stock market.$S&P 500 Index (.SPX.US)$On August 1st, 2nd, and 5th, the market fell for three consecutive trading days, totaling a 6.1% decline.

The replay of mistakes that I have witnessed over the decades is so apparent that I can't help but list them below.

What is the underlying cause of market volatility?

In the first two days of August, I was still in Brazil, where people often asked me to explain the cause of the sudden crash. I referred them to my 2016 memo "on the couch".

One of the main points is that in the real world, things fluctuate between "pretty good" and "not so good," but in investing, perspectives often swing between "perfect" and "hopeless." This captures 80% of what you need to know on this topic.

If the reality changes so little, why does the evaluation of value (securities prices should be like this) change so much?

The answer is closely related to changes in emotions. Just as I wrote in a memo 33 years ago,

The emotional fluctuations in the securities market are similar to the swing of a pendulum... swinging between excitement and frustration, between celebrating positive developments and being obsessed with negative developments, resulting in price swings that are either too high or too low.

This kind of volatility is one of the most reliable characteristics in the investment world. Investor psychology seems to be more extreme rather than moderate. (April 1991)

Emotional fluctuations can greatly change investors' perceptions of events, leading to drastic price fluctuations.

When prices plummet like they did earlier this month, it is not because the situation suddenly got worse, but because people believe the situation is very bad.

Several factors contribute to this process:

Increased awareness of one side of the emotional ledger and awareness of the other side of the emotional ledger

Tends to overlook the other side of things;

And people tend to interpret things in a way that conforms to the mainstream narrative.

This means that during economic prosperity, investors will focus on the positive factors, ignore the negative ones, and make favorable interpretations of things.

Then, when the pendulum swings, they will do the opposite, creating a dramatic effect.

An important fundamental idea in economics is the theory of rational expectations, as described by Investopedia:

Rational expectations theory... considers that individual decisions are based on three main factors: human rationality, available information, and past experience.

If security prices really were the result of rational, unemotional evaluation of data, then a negative piece of news might cause the market to fall a bit, and the next negative news would cause the market to fall further, and so on.

But the reality is different.

We see that optimistic markets can ignore individual bad news until the bad news reaches a critical point. Then the optimists surrender, and the collapse begins.

Rudiger Dornbush's quote about economics is very applicable here: "...things take longer to happen than you think, and then they happen much faster than you thought." Or as my partner Sheldon Stone said, "The balloon deflates much faster than it inflates."

The nonlinear nature of this process indicates that there is something entirely different from rationality.

In particular, like many other aspects of life, cognitive dissonance plays an important role in the psyche of investors. The human brain naturally tends to ignore or reject input data that contradicts previous beliefs, and investors are particularly adept at this.

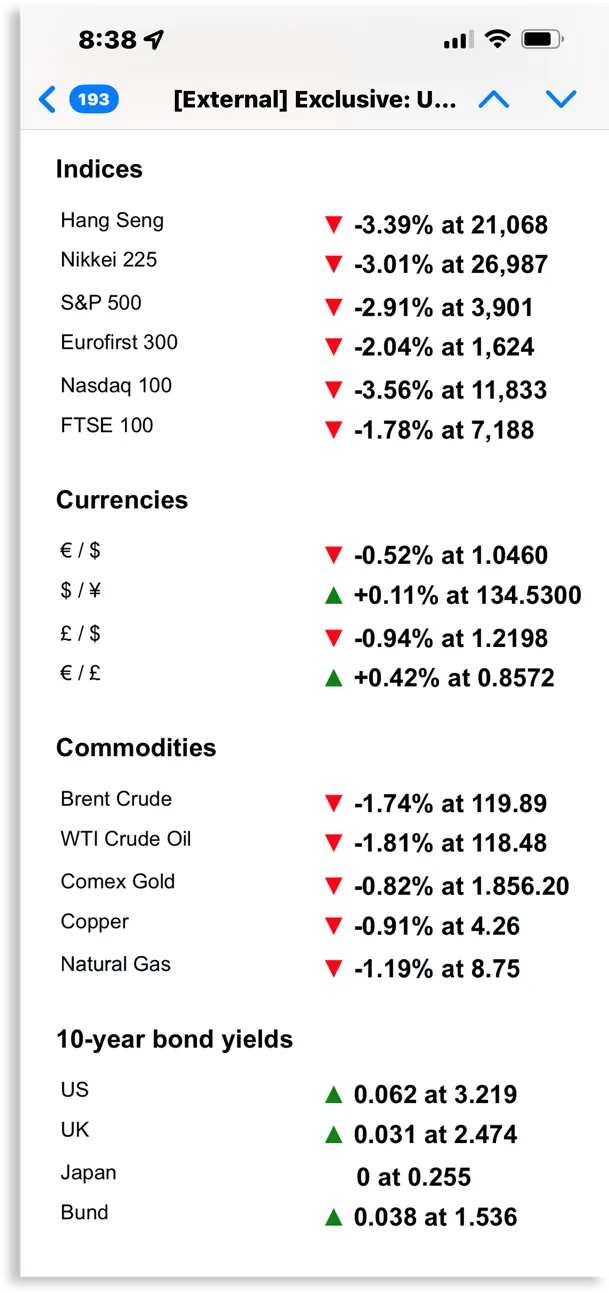

I have been waiting for the opportunity to share the screenshot from June 13, 2022, when we discussed this topic of irrationality:

It was a tough day for the market: due to the actions of the Fed and other central banks, interest rates rose, putting enormous pressure on asset prices.

But look at this table. The stock indices of every country fell sharply. Every currency fell against the US dollar. Every commodity fell. Only one thing rose: bond yields...which means that bond prices were also falling.

Wasn't there a single asset or country that didn't fall in value that day?

Gold, should it perform well during difficult times?

In my opinion, during significant market volatility, no one engages in rational analysis or makes distinctions. They simply throw the baby out with the bathwater, primarily due to emotional fluctuations.

As the saying goes, 'In times of crisis, all correlations tend toward 1.'

In addition, the data in the table also reveals another phenomenon that frequently occurs during extreme trends: contagion.

The US market encounters issues; European investors see it as a sign of trouble, so they sell; Asian investors sense the negative situation about to happen, so they sell overnight; and when US investors enter the market the next morning, they are frightened by the negative developments in Asia, confirming their pessimism, so they sell.

This is very similar to the whisper game we played when we were kids: information may be misinterpreted during transmission, yet it still encourages baseless actions.

When there is intense emotional fluctuations, meaningless remarks also receive attention.

During the three-day decline at the beginning of this month, it was observed that foreign investors sold more Japanese stocks than they purchased, and investors' reaction seemed to imply something.

But if foreigners overall sell, then Japanese investors overall must also be buying. Should these two phenomena be considered more important than the other? If so, which one is more important?

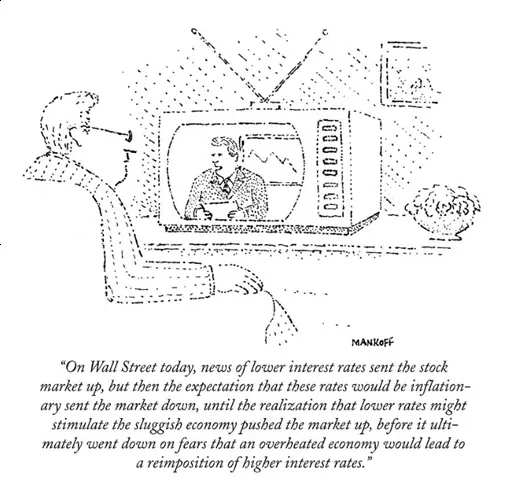

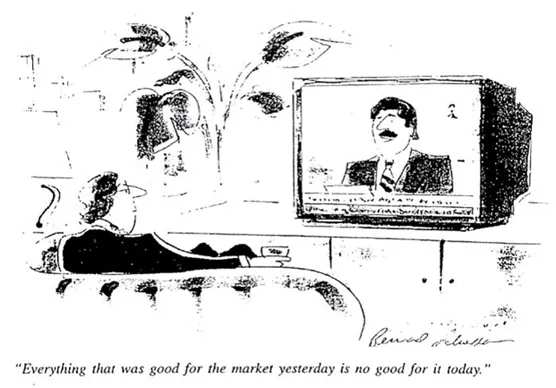

According to rational analysis, what makes it more complicated is that most developments in the investment field can be interpreted as positive or negative, depending on the prevailing sentiment at the time.

Another classic cartoon summarizes this ambiguity with fewer words. It is very suitable for expressing the volatility of the market, which is also the inspiration for this memorandum.

Another reason for misjudgment is the tendency of investors to have optimistic inclinations and wishful thinking.

General investors, especially stock investors, must be optimists by definition. Who, apart from those with positive expectations (or a strong desire to increase wealth), would be willing to give up their funds today in the hopes of getting more returns in the future?

Warren Buffett's deceased partner, Charlie Munger, often quoted the words of the ancient Greek politician Demosthenes: "Nothing is easier than self-deception. For what each man wishes, that he also believes to be true."

A good example is the "blonde thinking": to believe that the economy will neither be strong enough to trigger inflation nor weak enough to fall into a recession. Sometimes things develop this way - it may be the case now - but it is far less frequent than investors imagine.

A tendency towards positive expectations encourages investors to take proactive actions. If these actions are rewarded when times are good, it usually generates even more positive behavior.

Investors rarely realize that: (a) the emergence of good news is limited, or (b) the rise may be too strong, leading to an inevitable decline.

Over the years, I have quoted Warren Buffett's words to warn investors to restrain their enthusiasm: "When investors ignore the fact that the average profit growth of companies is 7%, they often find themselves in trouble."

In other words, if the average profit growth of a company is 7%, then if the stock rises 20% per year for a period of time (just like the entire 1990s), shouldn't investors start to worry?

I think this quote is very good, so I asked Warren Buffett when he said it. Unfortunately, he replied to me that he never said it.

But I still think it is an important warning.

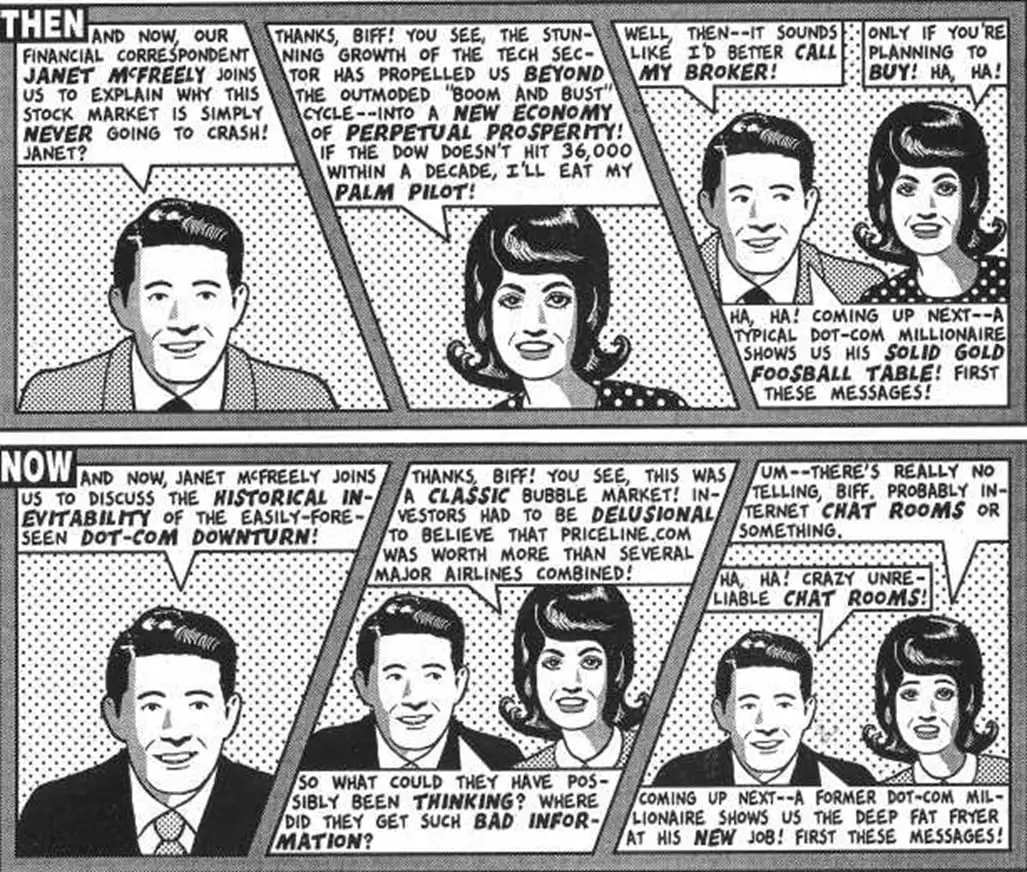

This inaccurate memory reminds me of one of the most important reasons why John Kenneth Galbraith sharply mentioned financial mania: "Financial memory is extremely short."

It is this characteristic that allows optimistic investors to take positive actions without worrying about the consequences of their behavior in the past. It also makes it easy for investors to forget past mistakes and invest recklessly based on the latest miraculous developments.

Finally, if there are immutable rules—like gravity—that can be expected to produce the same results forever, then the investment world may not be so unstable.

But there is no such rule. Because the market is not based on natural laws, but on the unpredictable nature of investor psychology.

For example, there is a long-standing saying that we should "buy on rumors, sell on news". Meaning, the appearance of favorable expectations is a buying signal, as expectations tend to continue to rise. However, when the news appears, this situation ends because the upward momentum has already been realized and there are no other good news to boost the market.

But in an environment of carefree attitudes a month ago, I told my partner Bruce Karsh that the mainstream attitude may have turned into "buy on rumors, buy on news". In other words, investor behavior seems to always be a good time to buy.

Rationally speaking, people should not count the possibility of a favorable event into the price twice: once when the event is likely to occur, and once when the event happens.

But enthusiasm can override human nature.

Another example of a lack of meaningful guiding principles can be seen from the oldest clipping in my file.

The continued consolidation and rotational patterns indicate that more emphasis should be placed on buying stocks in relative weakness and selling stocks in relative strength. This is in stark contrast to some periods where emphasis on relative strength has been proven effective. (Loeb, Rhoades & Co., 1976)

In short, sometimes the stocks with the biggest price increases are expected to continue to rise the most, and sometimes the stocks with the smallest price increases are expected to rise the most.

Many people might say 'something strange.'

In short: there are very few effective rules that investors can follow. Outstanding investments always come down to skillful analysis and excellent insight, rather than sticking to tradition.

Changeable psychology, distorted perception, overreaction, cognitive dissonance, rapid spread, irrationality, wishful thinking, forgetfulness, and lack of reliable principles...

This is a very long list of drawbacks.

They collectively constitute the main reasons for the extreme ups and downs in the market, leading to the dramatic fluctuations between them.

Ben Graham said that in the long run, the market is a weighing machine, evaluating the value of each asset and giving the appropriate price. But in the short term, it's just a voting machine, driving investor emotions to fluctuate dramatically, with little rationality, and the daily prices often do not reflect much wisdom.

I don't want to waste my efforts. I just want to reiterate some of the content I mentioned in my last two memos:

Especially during a decline, many investors perceive the market as wise and expect it to tell them what's happening and how to respond. This is one of the biggest mistakes you might make.

As Graham pointed out, the daily market is not a place for fundamental analysis, but rather a barometer of investor sentiment. You shouldn't take it too seriously.

Market participants have limited understanding of the true situation of the fundamentals, and any wisdom behind their trading decisions is overshadowed by their emotional fluctuations.

It is a big mistake to interpret the recent global decline as the market 'knowing' that it will face difficult times in the future. (From 'It’s Not Easy,' September 2015)

My bottom line is that the market does not evaluate intrinsic value every day, and it certainly does not do well during crises. Therefore, market trends cannot indicate the fundamentals.

Even in the best case scenario, when investors are driven by fundamentals rather than psychology, the market still reflects the value that participants believe, not the true value.

The market's understanding of value is not greater than that of ordinary investors. And the advice of ordinary investors obviously cannot help you become an above-average investor.

The fundamentals (prospects of the economy, companies, or assets) do not change significantly every day. Therefore, daily price changes are mainly related to: (a) changes in market sentiment, and (b) who wants to own or give up something.

The greater the daily price fluctuations, the more reasonable these two explanations become. Significant fluctuations indicate fundamental changes in market psychology.

Market volatility depends on the willingness of the most unstable participants. These people are willing to: (a) buy at a higher price than the original price when the news is positive and the market sentiment is high, and (b) sell at a lower price than the original price when the news is negative and the pessimistic sentiment is high.

Therefore, as I wrote in "On the Couch", the market needs to see a psychiatrist from time to time.

It is worth noting, as my partner John Frank pointed out, that there are relatively few people who drive stock prices up during a bubble period or drive them down during a collapse period compared to the total number of shareholders of each company.

When the stock of a company with a market cap of $10 billion a month ago trades at a price that implies a valuation of $12 billion or $8 billion, it does not mean that the entire company will change hands at these prices; only a small part will.

In any case, the impact of a few emotional investors on prices far outweighs the reality.

The worst thing is to join in when other investors get caught up in this irrational frenzy. The best way is to observe from the sidelines based on an understanding of how the market works.

But a better way is to see through the market's excessive reactions and adapt to it: sell to him when he is eager to buy, regardless of the price, and buy from him when he is eager to sell.

Below are Graham's recommendations when it comes to "Mr. Market":

If you are a cautious investor or a sensible businessman, would you determine the value of your $1000 equity in the company based on the information provided by Mr. Market every day? Only when you agree with his views or want to trade with him, you would do so.

When he offers an outrageously high price, you are willing to sell to him; likewise, when he offers a very low price, you are willing to buy from him. But for the rest of the time, it is best to consider the value of your equity based on the overall business operations and financial reports of the company.

In other words, the main task of investors is to pay attention to when the price deviates from the intrinsic value and find ways to deal with it.

Emotional? No! Rational analysis? Yes!

Editor/rice

从这个标题我们就应该知道他对此事的看法。

从这个标题我们就应该知道他对此事的看法。