Source: Qilehui.

Author: Value Watcher

Lou Simpson is the former Chief Investment Officer of Geico Insurance, a subsidiary of Berkshire Hathaway, and is referred to as one of the investment masters by Buffett.

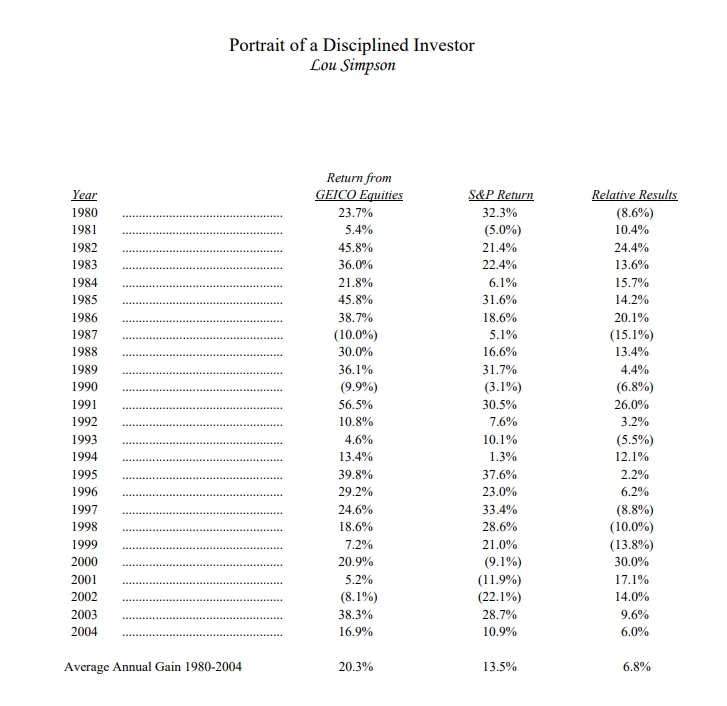

Lou Simpson, the former Chief Investment Officer of Geico Insurance under Berkshire Hathaway, was called "one of the investment masters" by Buffett. In the 2004 letter to shareholders, Buffett mentioned Simpson's impressive performance (see Figure 1).

From 1980 to 2004, the Geico Insurance investment portfolio managed by Simpson had an annualized composite return of 20.3%, which was 6.8 percentage points higher than the S&P index return during the same period. Simpson had independent investment decision-making authority at Geico Insurance without needing Buffett's prior approval.

From 1980 to 2004, the Geico Insurance investment portfolio managed by Simpson had an annualized composite return of 20.3%, which was 6.8 percentage points higher than the S&P index return during the same period. Simpson had independent investment decision-making authority at Geico Insurance without needing Buffett's prior approval.

Kellogg School of Finance Professor Robert Korajczyk interviewed Simpson to discuss his investment strategy.

Robert Kolarczyk: What do you think is the essence of your investment philosophy?

Simpson: The essence is simplicity. The foundation of investing in any area of the market is passive products, such asindex funds. This is accessible to any investor.

If you are a professional investor, the question is: how do you add value? The more you trade, the harder it is to add value, because you have to bear a lot of trading costs, not to mention taxes.

What we do is run a long-term investment portfolio consisting of ten to fifteen stocks. Most of them are American stocks with similar characteristics. Essentially, they are all excellent companies. They have high returns on capital, sustained good returns, and their leaders are committed to creating long-term value for shareholders while treating stakeholders correctly.

Kolarczyk: So you focus your investment on the best insights.

Simpson: You can only understand so many companies. If you have to manage 50 or 100 positions, then your probability of adding value will be much lower.

So far this year, we have bought a new position and we are seriously considering buying another one. I don't know what decision we will make. Our turnover ratio is 15%, 20%. In general, we will add one or two things while giving up one or two things.

Warren (Buffett) once said that you should consider investing as someone giving you a scorecard with 20 holes in it. Every time there is a change, you make a hole in the card. Once you've made 20 changes, you have to stick with what you have. The key to the problem is that every decision you make has to be very careful. The more decisions you make, the greater the likelihood of making mistakes.

One thing that many investors tend to do is to cut the flowers and water the weeds. They sell the winners and keep the losers, hoping the losers can turn around. In general, cutting the grass and watering the flowers is more effective. Sell the things that are not successful and let the successful ones continue to operate.

Corachick: Are investors afraid of missing out on good companies?

Simpson: If I made one mistake in managing investments, it was selling very good companies too early. Because generally, if you make good investments, they will last a long time. Of course, everything will change. Amazon is greatly changing the retail trade.

Corachick: What is the right balance between quantitative and qualitative skills in your investment approach?

Simpson: I think you need a combination of quantitative and qualitative skills. Most people now have quantitative skills. Qualitative skills will improve over time.

But, as Warren often says to me, 'Vague correctness is more important than precise incorrectness.' Everyone is talking about modeling, and modeling may be useful, but if you can achieve vague correctness, you will do well.

For example, one thing you need to determine is whether the company's leadership is honest and upright. Is their turnover rate high? Are they treating employees poorly? Is the CEO focused on long-term business operations or on the expected profits of the next quarter?

Colacicco: It sounds like qualitative skills can help you assess the adverse factors of a concentrated investment portfolio, namely concentration risk. What factors would you consider when you are concerned that an investment may go bust and harm your portfolio?

Simpson: We consider several factors. First, is this the same company as we previously determined? If you find that a company is different from what you thought before, that's a bad sign.

The second factor is management, which may also be different from what you imagined. Unfortunately, many managers are very short-sighted, which can be another reason to sell. This brings us back to the basic integrity and focus of the management.

The third factor is overvaluation, which is often the most difficult because you wouldn't buy what you're investing in at the current price, but you don't want to sell it because it's a very good company and you think the price has risen a bit too much. Perhaps it's worth holding for a while.

Colacicco: I think your investment style is very similar to Buffett's. Are there any interesting differences between you and Warren?

Simpson: The biggest difference between Warren and me is that Warren's job is much more challenging. He manages funds that are 20 times larger than ours. We manage $5 billion. In terms of stocks, he may have to manage $800, $900, or $100 billion. So if he wants to have a concentrated investment portfolio, he will have more limitations on what he can buy, and he does indeed achieve that.

Colacicco: You emphasize long-term focus and low turnover ratio. It seems true that the more trades there are, the lower the return.

Simpson: Yes, I think there is a strong correlation. There is also a negative correlation between the number of people involved in investment decisions and performance. If you have a lot of people involved, you typically let the least capable person make the decision because you need consensus.

One thing I tell people is that if you truly believe you cannot add value - and most people can't - then I think your basic investment product should be a low-cost passive product.

Kolachek: Is there a way for someone to be an active investor but only spend a few hours doing research on weekends?

Simpson: Maybe. But even among full-time trading professionals, most people cannot add value. Because you still have to pay fees and trading costs.

Yes, I think some people, with the right mindset, maybe some connections, and of course some luck, can outperform the large cap. However, if someone intends to invest based on hot tips, or listen to CNBC, or invest with the so-called financial managers of brokerage firms, I think it's a loser's game for them.

Editor/rice

1980年-2004年,辛普森管理的盖可保险投资组合,年化复合回报率为20.3%,高于同期标普指数回报率6.8个百分点。辛普森在盖可保险具有独立的投资决策权,事先无须征得巴菲特的同意。

1980年-2004年,辛普森管理的盖可保险投资组合,年化复合回报率为20.3%,高于同期标普指数回报率6.8个百分点。辛普森在盖可保险具有独立的投资决策权,事先无须征得巴菲特的同意。