Source: Smart investors.

Warren Buffett's grid theory is already well known in the investment community, but there are still not many people who can accurately grasp this theory.

Because it requires us to apply the general wisdom of various disciplines, build a large interdisciplinary knowledge network, and cross-validate the issues that need to be demonstrated in the network.

Buffett said that we should strive to master more knowledge of the stock market, finance, and economics, but we should not isolate this knowledge. Instead, we should consider it as part of the human knowledge treasure trove, including psychology, engineering, mathematics, physics, and so on.

Buffett said that we should strive to master more knowledge of the stock market, finance, and economics, but we should not isolate this knowledge. Instead, we should consider it as part of the human knowledge treasure trove, including psychology, engineering, mathematics, physics, and so on.

The world is always in a random walk, and the market is unpredictable. No single disciplinary thinking can effectively explain the changes. However, if the same conclusion is obtained through multiple different disciplines and dimensions in validating the same problem, the accuracy of investment decisions may be higher.

But energy is always limited. Buffett advises: First, learn mathematics, physics, and chemistry, plus one engineering course. In addition to mastering the basic principles of these four hard sciences, it is more important to cultivate one's precise logical thinking.

Based on this, master as many disciplines as possible, including psychology, physiology, accounting, management, economics, finance, political science, sociology, history, law, medicine, business, and many more.

Of course, he also said, 'You don't have to become an expert in all these fields. All you have to do is to grasp the really useful main ideas, understand them as soon as possible, and master them.'

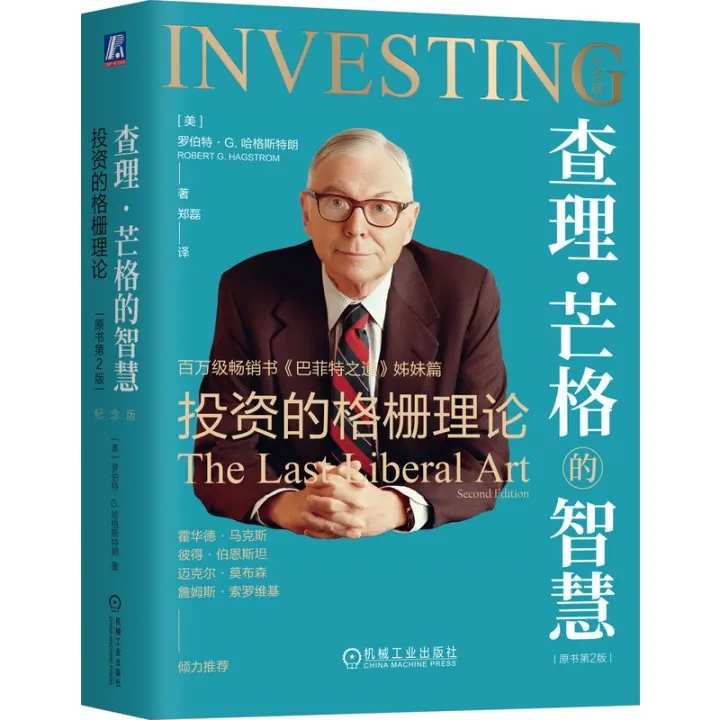

We have selected this article from the book 'Charlie Munger's Wisdom' written by Robert G. Hagstrom, hoping to help you better understand the lattice-model of thinking.

The introduction of this book uses a very interesting language story: 'The Fox and the Hedgehog.'

In a poem by the ancient Greek poet Archilochus, there is a phrase that roughly means: 'The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing.' The poet wanted to express that the fox is cunning and has many tricks to eat the hedgehog, but the hedgehog only needs one move to protect itself - curling its soft body into a hard and spiky shell.

However, the philosopher Isaiah Berlin breaks away from the fable story and says that the hedgehog and the fox can actually represent two types of people, two worldviews.

The fox is encyclopedic, knows many things, and often 'contradicts each other,' while the hedgehog seeks unity in everything. They understand the world in different ways and apply that understanding to their decision-making processes.

The so-called hedgehog is a person who sees everything as a nail when holding a hammer. They place all their life weight on a fulcrum of belief, attributing it to a large, centralized system and firmly believing in it.

On the other hand, the fox knows many truths, and even if these truths contradict each other, they can calmly handle them because the fox always maintains a reasonable doubt about the 'small' things they know. The fox opposes blindly believing in a specific dogma or principle, such as the hedgehog's knowledge of a big thing.

The fox knows many things and is not limited to large systems and ideologies, while the hedgehog relies on one brilliant move, being persistent, unwavering, and not adaptable.

If you have been exposed to Munger's latticework theory, you will find that he is like a fox because he knows too many "small" things, using one stake after another, one nail after another, bit by bit to build a "grid of thinking models", and under the training of associative thinking, construct a grand spiritual world.

The following is the main text:

In April 1994, at the Marshall School of Business, University of Southern California, Munger gave a rare lesson to students of Guilford Babcock's investment seminar.

At the beginning, Munger playfully said that he would play a little trick with the audience before formally starting the lecture. He did not discuss the stock market, but talked about "picking stocks as an application branch of general wisdom".

In the following one and a half hours, he challenged the students, broadening their horizons in the fields of markets, finance, and economics, and inspired them not to treat this knowledge as isolated disciplines, but as a knowledge system that combines physics, biology, sociology, psychology, philosophy, literature, and mathematics.

In this broader perspective, he believes that various disciplines are interrelated and that they are reinforced by each other in the process of integration.

A person who loves to think will obtain excellent thinking models from each discipline, draw inspiration from important ideas, and achieve a comprehensive understanding. Those who stubbornly cling to a certain discipline, even if they can succeed, will only be short-lived.

To illustrate his point more clearly, Charlie used an imagery term to describe this way of thinking: the lattice model. (Note: The word "Latticework" mentioned by Munger in 1994 can be understood as a "grid".)

"There are many models in your mind," he explained, "and you should classify and place your experiences, whether they are obtained directly or indirectly, in your grid model." So, the grid theory quickly spread in the investment community and became a simple symbol of identifying Munger's methods.

Munger often applies his mental grid. For example, at the Berkshire Hathaway annual meeting, he frequently quotes words from a book he just read to supplement Buffett's answers. These quotes may initially seem unrelated to investments, but after Munger's explanation, they immediately become relevant.

Charlie Munger's focus on other disciplines is purposeful. He firmly believes that by integrating thinking models from different disciplines, investors can achieve superior investment returns.

If the same conclusion can be reached from different disciplinary perspectives, the investment decisions made will be more accurate. That is the biggest gain - a more comprehensive understanding allows us to become better investors.

Furthermore, its influence goes beyond that. Those who strive to understand liberal arts wisdom can better navigate life. They can become not only good investors, but also good leaders, good citizens, good parents, good spouses, and beneficial mentors.

The regret of higher education.

How can we gain liberal arts wisdom? Simply put, it is a gradual process. First, acquire valuable concepts, or models, from various fields of knowledge, and then learn how to identify similar models. The former is self-learning, and the latter is learning to think and view problems from different perspectives.

Gathering knowledge from various disciplines may seem like an impossible task. Fortunately, you don't need to become an expert in every field. You just need to learn the basic principles, which Charlie calls "the great ideas," and truly master them to use them to your advantage.

At this point, it is often heard such doubts: "Isn't this something that higher education should do - teaching us important concepts that have developed over the past few centuries?" Of course it is.

Most educators will passionately tell you that the best, perhaps the only, way to cultivate talents is through a curriculum based on the arts and sciences of universities. Few people disagree with this. However, in real life, our society leans more towards depth of knowledge rather than breadth.

This is completely understandable. Because students and their parents invest money in higher education, they expect this investment to provide good job opportunities immediately after graduation.

They know that most corporate recruiters require employees to be able to contribute to the company immediately with their professional knowledge. It is not surprising that today's students refuse to accept a broad arts and sciences education in addition to their professional knowledge. This is certainly understandable. But, as I said, I don't think it's a good idea.

Franklin: History can give you all the useful knowledge

In the summer of 1749, subscribers to the Pennsylvania Gazette received a booklet written by the publisher of the newspaper, Benjamin Franklin, in addition to the daily newspaper. In this booklet, titled "Advice to Pennsylvania Youth About Their Education", he expressed regret that "young people in this state have not received a college education."

Young people from Connecticut and Massachusetts have long been able to enroll in Yale and Harvard, and Virginians have William & Mary College, while students from New Jersey can attend the College of New Jersey (later renamed Princeton University).

However, as the largest and most prosperous city in the United States, Philadelphia, known as the "Athens of America," did not have a college. In this booklet, Franklin proposed a solution to this problem by establishing the Philadelphia Public College.

In that era, Franklin's ideas were unique. The Harvard, Yale, Princeton, William & Mary, and other colleges at the time were used to train clergy, and their curriculum focused on the study of classical works, rather than practical courses to prepare young people for future business and public service.

Franklin hoped that the Philadelphia Public College could balance both, emphasizing the traditional classical field (as he put it, "decorating the facade") as well as practicality. "Regarding the education of young people," he wrote, "if we can teach them useful things and also teach them how to decorate the facade, that would be great."

However, knowledge is endless while time is limited, so they should learn the most essential and useful knowledge in several professions they will engage in the future.

Today, the Philadelphia Public College proposed by Franklin has become the University of Pennsylvania. Dr. Richard Beeman, a former dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, describes Franklin's achievements as follows: "Benjamin Franklin proposed the first modern curriculum," he explains, "and it was proposed at the best time."

In the 18th century, with the continuous emergence of new discoveries in mathematics and natural sciences, the knowledge foundation of the world experienced an explosive breakthrough, and the Greek, Latin, and Bible in traditional curricula could no longer explain this new knowledge.

Franklin suggested that these new areas be included in the curriculum of the public college, and then he went one step further by suggesting that students acquire the necessary skills in order to succeed in business and public service in the future. Once students have mastered these basic skills— including writing, drawing, public speaking, and arithmetic at the time—they would be able to concentrate on acquiring knowledge.

"Almost all useful knowledge can be obtained through the study of history," Franklin wrote. But what he meant was much broader than what we commonly refer to as the discipline of history. "History" includes everything that is meaningful and valuable.

Franklin advocated that young people learn history, which means they should learn philosophy, logic, mathematics, religion, government, law, chemistry, biology, medical care, agriculture, physics, and foreign languages.

For those who are worried about whether these heavy learning tasks are really necessary, Franklin's answer is: this is not a burden, but a gift from God. If you read the history of various countries, you will have a better understanding of humanity.

Benjamin Franklin is the initiator of liberal arts education. As pointed out by Biman, "His success in education is based on three principles.

The first is that students must learn basic skills: reading, writing, arithmetic, physics, and public speaking. Then guide students to enter the ocean of knowledge, and finally cultivate their thinking habits by guiding students to discover the connections between different knowledge.

From Franklin's suggestions to today, 250 years later, the American education community has been discussing the best way to educate young people to think.

Despite various shortcomings, our education system is still doing well in providing skills and imparting knowledge - these are the first two important principles mentioned by Franklin. What is lacking is the third principle: the "thinking habits" of exploring between different knowledge.

We can change this situation. Even if we have long been away from school, we can still, in our own way, find the connections in different fields of knowledge - the kind that you truly understand.

Cultivating Franklin-style "thinking habits" and adopting Professor Biman's incisive words is the key to acquiring Charlie Munger's "general wisdom".

However, it is easier said than done. For most of us, this is contrary to our existing thinking methods. After spending years studying a specific discipline, we are now required to self-study knowledge in other disciplines. We are asked not to limit ourselves to the subjects we have studied, to break through our professional barriers, and look at the surrounding world.

For investors, the return on doing so is lucrative. When you cross the barriers in front of you, you will be able to observe similar situations happening in other fields and discern different modes of thinking.

Then, one concept will be reinforced by another concept, and this concept will be reinforced by a third concept, constantly developing. You will find yourself on the right path. The key is to find the connections between different ways of thinking. Fortunately, our human brain has always worked this way.

Wisdom is the ability to learn and master the "connections".

Edward Thorndike was the first person to discover what we now call the stimulus-response phenomenon. When a connection is formed between a stimulus and a response, learning behavior occurs.

Thorndike later summarized in a research paper published in 1901 with Robert Woodworth that learning in one domain does not transfer to learning in another domain. They pointed out that learning can only transfer when there are similar elements between the original domain and the new domain.

From this perspective, learning new concepts, rather than changing a person's learning ability, is more about enriching their knowledge structure. We learn new subjects not because we become better learners, but because we become better at recognizing various patterns.

Edward Thorndike's theory of learning, known as connectionism, became a core theory of contemporary cognitive science, which studies how the brain works - how we think, learn, reason, remember, and make decisions.

The theory of connectionism in psychology originates from Thorndike's research on the stimulus-response pattern. It suggests that learning is a trial-and-error process, where positive responses to new situations (stimuli) actually change the connections between brain cells.

In other words, the learning process affects the synaptic connections between neurons. When the brain receives new information and identifies similar patterns within it, these synapses continuously adjust to adapt and accept this new information. The brain can link related connections into a loop and transfer what is learned to similar situations.

Therefore, intelligence can be seen as a person's ability to learn and master more of these connections.

Due to the powerful new information system - artificial neural networks - which is primarily based on connections, connectionism has gained widespread attention from business leaders and scientists. This network is more commonly known as a neural network, as people attempt to replicate its working principle, which is closer to that of the human brain compared to traditional computers.

We can think of the brain as a neural network, and artificial neural networks are computers that mimic the structure of the brain: they include hundreds of processing units (similar to neurons) that are interconnected to form a complex network.

(It is surprising that neurons are much slower in speed than silicon chips by several orders of magnitude, but the brain compensates for this speed limitation through a large number of connections to improve efficiency.)

The establishment of grid thinking

The Santa Fe Institute in New Mexico integrates research and education, attracting physicists, biologists, mathematicians, computer scientists, psychologists, and economists to study complex adaptive systems.

These scientists are trying to understand and predict the immune system, central nervous system, ecology, economics, and stock market, and they have a keen interest in innovative thinking.

(Editor's note: Bill Miller's change of attitude towards the internet and technology stocks, also related to his visits to the Santa Fe Institute since 1992.

The Santa Fe Institute, which studies complex systems science, has provided Bill Miller with a different source of information for investment research. After purchasing blue chip stock IBM in 1993, he mentioned that "technology will disrupt other industries, and without understanding the risks involved, there is a possibility of making investment decisions based on ignorance".

John H. Holland, a interdisciplinary professor (psychology, engineering, and computer science) at the University of Michigan, is a frequent visitor to the Santa Fe Institute and has given many speeches on innovative thinking.

According to Holland's theory, innovative thinking requires us to master two important steps.

Step 1, we need to understand the basic framework of the knowledge we acquire; Step 2, we need to understand how to use analogies and their benefits.

You will find that Step 1 is identical to the first half of what Charlie Munger said about acquiring worldly wisdom. The ability to connect various mental models and benefit from them indicates that you have a basic understanding of each model in the grid.

It is useless to mix mental models together if you do not understand how each model works and the phenomena it describes. Remember that while you don't have to be an expert in each model, you still need to have the necessary basic knowledge of these models.

Step 2 is to look for analogies - which may seem strange at first, especially when you think back to the English class you took in 9th grade. The simplest definition of an analogy is conveying meaning in an unconventional and indirect way.

When we say "work is hell", we are not expressing that we are burned by the fierce fire all day and have to eradicate the ashes; but we mean that we are really tired of going to work today. Analogy can be used as a concise, memorable, and vivid method to express emotions.

Furthermore, analogy can not only be expressed through language, but also through thoughts and actions.

However, Holland said that analogy is not just a vivid way of expression, it is even more profound than the thinking process it represents, and it can help us input ideas into models. And this represents innovative thinking.

In the same way, analogy can explain a new concept by comparing it to a familiar one, describe a thought with a simple model to help us understand a similar complex thought, and even inspire new ideas.

According to the memorable series of reports in the magazine "Frontier", James Burke wrote in his book "Connections" that in many cases, inventors created new inventions because they observed similarities between the desired result (target) and the previous inventions (source). The automobile is the most classic example.

The carburetor of the car is related to the perfume bottle, and the perfume bottle is related to an Italian in the 18th century who wanted to use steam. Alessandro Volta's electron gun was originally invented to test the purity of air, and 125 years later, it was used to ignite the fuel in the carburetor.

The gears of the car originate from water wheels, and the pistons and cylinders of the engine can be traced back to Thomas Newcomen's water pump designed for coal mine drainage systems.

Therefore, each major invention is connected to an early idea, which is the pattern that can inspire the original idea.

For us, the main topic (symbol) we want to understand is the stock market or the economy. Over the years, we have accumulated numerous source models in the financial field to explain phenomena in the stock market and economy, but these source models often fall short. The performance of the market and economy remains a mystery to this day.

Now is the time to expand into different areas to study our perception of the market. By exploring more areas, we are more likely to find common mechanisms to unravel the mystery. The innovative thinking we pursue typically arises from the combination of two or more different thinking models.

The grating thinking pattern itself is an analogy, and a simple one at that. Everyone knows what a grating is, many people have had intimate contact with gratings. We use them to decorate fences, build pergolas, and make grape trellises. Using a grating to handle a series of thinking frameworks is just a slight extension of its utility.

Like many ideas that seem simple at first glance, the more we understand the analogy of the grating theory, the more we realize its complexity, and the harder it is to view it as a purely cognitive model framework.

I myself am also using different analogies to express the concept of the grating model.

Facing those with a high-tech background, I often compare the process of creating a grating model to designing a central nervous system network, and they quickly understand the powerful energy a grating model may possess. Psychologists easily link the grating theory to connectionism, while educators associate it with the brain's ability to seek and discover new patterns.

When facing those who are good at exploring human nature, I will talk about the value of analogies in order to expand our understanding of analogies. Others like myself, who are not from the scientific community, often strongly react to descriptions such as small light bulbs between the gratings.

One afternoon, as I gazed at the garden fence, I had a sudden insight. The fence had a decorative lattice, with the fence divided by posts into sections, and the lattice divided by the fence into blocks.

As I looked at the fence and pondered the model of thinking, I slowly began to understand: each grid is like a field of knowledge; the one near the garage is psychology, and the one next to it is biology, and so on.

The connection between two grids can be seen as the intersection of disciplines. Next, in the extraordinary reasoning process of the brain, I suddenly thought of the Christmas decorations outside the door, and then I imagined the miniature light bulbs on the decorating nodes.

If I urgently want to know the market trend or make an investment decision, I will arrange the uncertain factors in a grid thinking pattern.

First, I use the biological thinking model to predict, and I may see many light bulbs lit. Then, in the next section, such as psychology, there are other bulbs lit. When I observe that the bulbs in the 3rd and 4th sections are also lit, I have confidence in myself because the initially uncertain idea has now been verified.

On the contrary, if I don't see any lit bulbs when considering a problem, I will see it as evidence that the approach is not feasible.

This is the power of grid thinking models, it can not only solve small problems like stock selection. It can help you to comprehensively understand the forces of the market - new industries and trends, emerging markets, cash flow, international market changes, economic situations, and the reactions of market participants.

Munger: The fun of creating a grid thinking pattern will not end.

Charlie Munger once gave a stunning lecture at the University of Southern California (link added), telling finance students to see investment as part of common sense wisdom.

Two years later, at Stanford Law School, he introduced his basic view for the first time: continuous success belongs to those who first construct a grid thinking model, and then think in a holistic and diverse way.

He reminded us: this may take some effort, especially when you have already received professional education. Once these thinking models are ingrained in your mind, you will be able to rationally deal with various situations.

It is clear that Benjamin Franklin also thought so.

I believe that those who are willing to connect different thinking models are more likely to achieve extraordinary investment returns. When this happens, the "extraordinarily powerful force" that Charlie mentioned will occur.

This is not a problem of one plus one equals two; it has the power of critical mass explosion, which is the "super powerful force" that Charlie mentioned.

When answering Stanford students' questions about how to develop thinking patterns, he said:

"General wisdom is very, very simple, with some corresponding principles and real wisdom, and the process of finding them is very interesting. It is important that this joy will not end. More importantly, we can gain a lot of wealth from it, I have tested it myself.

I hope what you do is not difficult, and the rewards are very generous... Having this wisdom will be very helpful to your business, giving you legal protection, and making your life meaningful. Let your love be more fulfilling... It enables you to help others and yourself, making life full of joy.

Editor/rice

芒格说,要努力掌握更多股票市场、金融学、经济学知识,

芒格说,要努力掌握更多股票市场、金融学、经济学知识,