Source: IN Coffee Moutai, standing on the wave crest, is still the "original self" in Duan Yongping's eyes. "In the companies that I know better (with annual profits of more than $1 billion), I think companies that will have higher total profits in the next 10 years than in the past 10 years may include:"

According to Xinhua News Agency, on July 21st local time, US President Biden announced his withdrawal from the 2024 presidential election. After announcing his withdrawal, Biden said he would fully support Vice President Harris in obtaining the Democratic Party's nomination.

Since the debate with the current President Biden, especially after being shot at a rally, the call for former President Trump to return to the White House has continued to rise... The overseas investment institution's predictions have fluctuated greatly.

Some people mentioned that Trump will not forget the company that restricted his social media accounts when he was about to leave office, and some analysts believe that he will cut government projects and thus be unfavorable to new energy, and some institutions propose that the more split the capital markets, the better they perform, and so on.

We all remember that when Trump was unexpectedly elected for the first time, it was considered the end of the world, and risk premiums skyrocketed, the stock market once collapsed, but within a few hours, the market changed its mind and opened the Trump bull market.

Eight years have passed, and if Trump is elected this time, although the unexpectedness has greatly reduced, investors are still difficult to avoid emotional roller coasters.

In the latest investment memo on July 17, Howard Marks took inspiration from an article on elections, focusing on why forecasting in the three areas of politics, economics, and capital markets often fails.

The common feature of these three areas is that they are influenced by psychological fluctuations, irrationality and randomness, so there is no certainty at all.

Howard also mentioned a view that he had never written on, that there is a seemingly false connection between money and wisdom.

"When people become rich, others will think that they are smart; when investors succeed, people often think that their wisdom can also have insights in other fields, even successful investors themselves will have this feeling."

And he believes that "the success of investors may be the result of a series of lucky events or favorable conditions, rather than the result of any special talent. They may be smart, or they may not be smart, but successful investors often do not know more than most people about topics outside of investment."

The period before the November election is destined to be a long process.

Perhaps we should learn from Dr. John Drumpf, who deliberately read the Wall Street Journal a few days later, or perhaps we should repeatedly recite Buffett's words while making full preparations and acting cautiously, "Uncertainty is the friend of long-term value buyers."

The Stupidity of Certainty

By Howard Marks

I usually have various inspirations for writing memos, and the inspiration for this memo came from an article in The New York Times on Tuesday, July 9th.

What caught my attention at the time were a few words in the subtitle: "She has no doubt."

The speaker in the article was Ron Klain, Biden's former chief of staff, and the theme of the article was whether President Biden should continue to seek re-election. The "she" in the subtitle refers to Jen O'Malley Dillon, Biden's campaign team leader.

The article also quoted her words on June 27th, a few days before the debate between Biden and former President Trump: "Biden will win, there is nothing else to say."

The theme of my memo is not about whether Biden will continue to run for president or drop out of the race, nor about whether he will win if he continues to run, but that no one should be 100% certain about anything.

Considering that Biden's candidacy is still uncertain, this will serve as another "short" memo of mine.

This topic reminds me of a time when I heard a very experienced professional express absolute certainty about his experience.

A recognized diplomatic affairs expert told us that "the likelihood of Israel 'killing' Iran's nuclear capability before the end of the year is 100%." He looked like a real insider, and I had no reason to doubt him.

I remember it happened in 2015 or 2016. If I had to defend him, he didn't say which year it was.

As I pointed out in my September 2009 memorandum "The Illusion of Knowledge," macro forecasters cannot correctly incorporate all the many variables we know will affect the future, as well as the random effects we know little or nothing about.

That's why, as I have written in the past, investors and others who are affected by macro future changes should avoid using words such as 'will,' 'will not,' 'must,' 'cannot,' 'always,' and 'never.'

I. Political Field

Recalling the eve of the 2016 presidential election, almost everyone was certain of two things:

(a) Hillary Clinton would win;

(b) If Donald Trump won by some stroke of fate, the stock market would crash.

Even the least confident scholars thought that Clinton had an 80% chance of winning, and other predictions continued to rise on this basis.

However, Trump won, and the stock market rose more than 30% over the next 14 months.

Most forecasters' reaction was to adjust their models and promise to do better next time.

My conclusion is: if this is still not enough to make you believe that: (a) we don't know what will happen; (b) we don't know how the market will react to what actually happens, then I don't know what will convince you.

Referring back to the present, even before the highly anticipated presidential debate three weeks ago, I didn't know anyone who expressed too much confidence in the outcome of the upcoming election.

Ms. O'Malley Dillon mentioned at the beginning of this article may now soften her position that Biden will win, explaining that the results of the debate have surprised her.

But that's the point! We don't know what's going to happen.

Indeed, there is randomness!

When things develop as expected, people say they knew what would happen early on. When things develop differently from expected, they say the forecast would have been correct if there had been no unexpected situations.

However, in either case, unexpected situations may occur, that is, the forecast may be incorrect.

The difference is that in the latter case, unexpected situations have occurred, while in the former case, the possibility of unexpected situations cannot be denied.

II. Macroeconomic Domain In 2021, the Federal Reserve believed that the inflation that was happening at the time would prove to be "transitory," defining it as temporary, non-structural, and possibly self-correcting inflation. My opinion is that if you stretch the timeline long enough, the Federal Reserve may be proven right. Inflation may self-correct in three to four years, on the condition that: (a) The pandemic relief fund that causes an increase in consumer spending is depleted; (b) The global supply chain resumes to normal. (However, there is also a logic here: If the economic growth rate is not slowed down, it may lead to inflation expectations/psychology in these three to four years, which will require stronger action). However, since the Federal Reserve's view was not confirmed in 2021, waiting any longer is untenable. Therefore, the Federal Reserve has been forced to launch one of the fastest rate-hiking campaigns in history, which has had far-reaching implications. In mid-2022, the Fed's rate-hiking measures are almost certain to trigger an economic recession. The sharp rise in interest rates will have an impact on the economy, which is also reasonable. History explicitly tells us that squeezing monetary policy often leads not to a "soft landing," but rather to economic contraction. However, the fact is that the economy has not experienced a downturn. On the contrary, by the end of 2022, the market consensus had shifted to: (a) The easing of inflation provides room for the Fed to start cutting rates; (b) Rate cuts will help the economy avoid a recession, or ensure any contraction is mild and short-lived. This optimism ignited the stock market rally at the end of 2022 and continues to this day. However, the 2023 rate cut leading to a rebound in the market did not happen. In December 2023, the "dot plot" representing the views of Fed officials showed expectations for three rate cuts in 2024, but the market optimists directly doubled it, expecting six rate cuts. More than half of 2024 has passed, and inflation remains high with no rate cuts. The market unanimously believes that the first rate cut will come in September, and the stock market continues to reach new highs in this sentiment. The current optimists may say, "We are right. Look at the gains!" However, they are utterly wrong about the rate cuts. To me, this is just another reminder that we do not know what will happen or how the market will react. My favorite economist, Conrad DeQuadros of Brean Capital, has provided an anecdote for economists: I will use the Philadelphia Fed's Anxiety Index (the probability of the actual GDP declining in the next quarter) as an indicator of the end of a recession.

In 2021, the Federal Reserve believed that the inflation that was happening at the time would prove to be "transitory," defining it as temporary, non-structural, and possibly self-correcting inflation. My opinion is that if you stretch the timeline long enough, the Federal Reserve may be proven right. Inflation may self-correct in three to four years, on the condition that: (a) The pandemic relief fund that causes an increase in consumer spending is depleted; (b) The global supply chain resumes to normal. (However, there is also a logic here: If the economic growth rate is not slowed down, it may lead to inflation expectations/psychology in these three to four years, which will require stronger action). However, since the Federal Reserve's view was not confirmed in 2021, waiting any longer is untenable. Therefore, the Federal Reserve has been forced to launch one of the fastest rate-hiking campaigns in history, which has had far-reaching implications. In mid-2022, the Fed's rate-hiking measures are almost certain to trigger an economic recession. The sharp rise in interest rates will have an impact on the economy, which is also reasonable. History explicitly tells us that squeezing monetary policy often leads not to a "soft landing," but rather to economic contraction. However, the fact is that the economy has not experienced a downturn. On the contrary, by the end of 2022, the market consensus had shifted to: (a) The easing of inflation provides room for the Fed to start cutting rates; (b) Rate cuts will help the economy avoid a recession, or ensure any contraction is mild and short-lived. This optimism ignited the stock market rally at the end of 2022 and continues to this day. However, the 2023 rate cut leading to a rebound in the market did not happen. In December 2023, the "dot plot" representing the views of Fed officials showed expectations for three rate cuts in 2024, but the market optimists directly doubled it, expecting six rate cuts. More than half of 2024 has passed, and inflation remains high with no rate cuts. The market unanimously believes that the first rate cut will come in September, and the stock market continues to reach new highs in this sentiment. The current optimists may say, "We are right. Look at the gains!" However, they are utterly wrong about the rate cuts. To me, this is just another reminder that we do not know what will happen or how the market will react. My favorite economist, Conrad DeQuadros of Brean Capital, has provided an anecdote for economists: I will use the Philadelphia Fed's Anxiety Index (the probability of the actual GDP declining in the next quarter) as an indicator of the end of a recession.

My view is that if stretched out long enough, the Federal Reserve may be proven correct. However, since the Federal Reserve's view was not confirmed in 2021, waiting any longer is untenable. Therefore, the Federal Reserve has been forced to launch one of the fastest rate-hiking campaigns in history, which has had far-reaching implications.

Inflation may self-correct in three to four years, on the condition that:

(a) The pandemic relief fund that causes an increase in consumer spending is depleted;

(b) The global supply chain resumes to normal. (However, there is also a logic here: If the economic growth rate is not slowed down, it may lead to inflation expectations/psychology in these three to four years, which will require stronger action).

However, since the Federal Reserve's view was not confirmed in 2021, waiting any longer is untenable. Therefore, the Federal Reserve has been forced to launch one of the fastest rate-hiking campaigns in history, which has had far-reaching implications.

By mid-2022, the Fed's interest rate hike is almost certain to trigger an economic recession.

History explicitly tells us that a tight monetary policy often leads not to a "soft landing," but rather to economic contraction.

However, the fact is that the economy has not experienced a downturn.

On the contrary, by the end of 2022, the market consensus had shifted to:

(a) The easing of inflation provides room for the Fed to start cutting rates;

(b) Rate cuts will help the economy avoid a recession, or ensure that any contraction is mild and short-lived.

This optimism ignited the stock market rally at the end of 2022 and continues to this day.

However, the expected rate cut leading to a rebound in the market did not happen in 2023. In December 2023, the "dot plot" representing the views of Fed officials showed expectations for three rate cuts in 2024, but market optimists directly doubled it, expecting six rate cuts. More than half of 2024 has passed and inflation remains high with no rate cuts. The market unanimously believes that the first rate cut will come in September, and the stock market continues to reach new highs in this sentiment.

Current optimists may say, "We are right. Look at the gains!" However, they are utterly wrong about rate cuts.

To me, this is just another reminder that we do not know what will happen or how the market will react.

My favorite economist, Conrad DeQuadros of Brean Capital, has provided an anecdote for economists: I will use the Philadelphia Fed's Anxiety Index (the probability of the actual GDP declining in the next quarter) as an indicator of the end of a recession.

My favorite economist, Conrad DeQuadros of Brean Capital, has provided an anecdote for economists:

I will use the Philadelphia Fed's Anxiety Index (the probability of the actual GDP declining in the next quarter) as an indicator of the end of a recession.

When more than 50% of economists in the survey predict a decline in real GDP in the next quarter, the recession has ended or is nearing its end.

In other words, the only thing economists can be certain of is that they should not draw any conclusions.

III. Capital Markets

Few people can predict that the Fed will not cut interest rates in the next 20 months in October 2022. If this prediction makes them leave the market, they will miss the 50% increase in the S&P 500 index.

For the interest rate optimists, their judgment is completely wrong, but they may have made a lot of money now.

So, that's it, market behavior is difficult to judge correctly. I don't intend to list the so-called experts' mistakes in the market here.

Instead, I want to focus on why so many market forecasts have failed.

The trend of the economy and companies may tend to be predictable because their development trajectory...I should say...reflects the role of the mechanism.

In these fields, people may say "if we start from A, then we will reach B", and there is some certainty in this prediction. Or, in the case of unimpeded trends and valid inferences, there is a certain probability of correctness for this prediction.

But the volatility of the market is greater than that of the economy and companies. Why? Because the psychology or emotions of market participants plays an important role and there is unpredictability. To illustrate the degree of market volatility, let us continue to cite economist Conrad's data:

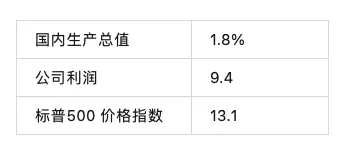

40-year standard deviation of annual percentage changes

Why do stock price fluctuations far exceed the economies and companies behind them? Why is market behavior so difficult to predict and often unrelated to economic events and company fundamentals?

The "science" of finance-economics and finance-assumes that each market participant is an economic man: they make rational decisions to maximize their economic interests. However, the key role played by psychology and emotions often leads to the error of this assumption.

Investors' emotional fluctuations are large, overwhelming the short-term impact of fundamentals.

Therefore, there are relatively few market forecasts that have been proven correct, and even fewer predictions that are "correct for the right reasons".

IV. Extension

Today, experts and scholars have made various predictions about the upcoming presidential election. Many of their conclusions seem to be reasonable and even convincing.

Some people believe that Biden should withdraw, while others believe that he should not; some people believe that he will withdraw, while others believe that he will not withdraw; some people believe that if he continues to participate in the election, he can win, while others believe that he is bound to lose.

Obviously, intellect, education level, data access and analysis ability are not enough to ensure making correct predictions. Because many of these commentators have these characteristics, and obviously, not all of them are correct.

I often quote the famous economist John Kenneth Galbraith's quote. He said: "There are two kinds of forecasters: those who don't know, and those who don't know they don't know. "I really like this sentence.

Another sentence from A Short History of Financial Euphoria. When discussing the reasons for 'speculative frenzy and programmatic collapse,' he discussed two factors that have been 'very little noticed in our time or in past times, one is the extreme brevity of financial memory.'

I have mentioned this several times in past memos.

But I don't remember that I have written about the second factor he mentioned, which Galbraith called 'the apparent connection between money and intelligence.'

When people become wealthy, others will think that they are very smart; when investors succeed, people often think that their intelligence and wit can achieve the same success in other areas. In addition, successful investors often believe in their own intelligence and express opinions on topics unrelated to investment.

However, the success of investors may be the result of a series of lucky events or favorable conditions, rather than the result of any special talent. They may be smart or not smart, but successful investors often do not know more than most people about topics other than investment.

Nevertheless, many people are still generous with their opinions, and these opinions are often highly praised by the public. This is part of the apparent connection.

Some of them are now speaking confidently on issues related to the election.

We all know some people whom we describe as 'often wrong but never in doubt.'

This reminds me of another of my favorite quotations from Mark Twain (perhaps with some reason): 'It ain't what you don't know that gets you into trouble. It's what you know for sure that just ain't so.'

In mid-2020, when various phenomena of the epidemic seemed to be under control, I slowed down the speed of writing memos, no longer writing them every week like I did in March and April.

In May, I wrote two memos unrelated to the epidemic, entitled 'Uncertainty' and 'Uncertainty II'. I discussed the theme of cognitive humility at great length.

These two memos are among my favorite topics, but they have not attracted much attention. I quoted a passage from 'Uncertainty' hoping to give everyone a reason to look back at them.

Here is an excerpt from the article that initially caught my attention on the topic of humility:

Li Ka-shing gave a speech at Shantou University in 2017 called 'Wishpower Life'. He said:

According to the author's definition, cognitive humility is the opposite of arrogance or conceit. In plain terms, it is similar to being open-minded. Intellectually humble people can have firm beliefs, but they are also willing to acknowledge their mistakes and be proved wrong on various things. (Alison Jones, Duke Today, March 17, 2017)

... In short, humility means saying 'I'm not sure,' 'others may be right,' or even 'I may be wrong.' I think this is a characteristic that investors must have; I clearly know that I like to associate with people who possess this characteristic...

If you start your speech with such a phrase, you won't encounter big trouble, including 'I don't know, but...' or 'I may be wrong, but...'

If we admit the existence of uncertainty, we will conduct due diligence before investing, repeatedly checking our conclusions, and acting cautiously. We will perform suboptimal optimization during prosperous times and are less likely to encounter 'shutdowns' or collapses.

Conversely, people who are absolutely certain may abandon the above behaviors, and once they make a mistake, as Mark Twain suggests, the result may be disastrous...

... To put it as Voltaire summed it up 250 years ago: doubt is not a pleasant condition, but certainty is absurd.

In short, there is no certainty in fields influenced by psychological fluctuations, irrationality, and randomness. Politics, economy and investing are such fields. No one can reliably predict the future in these areas, but many overestimate their abilities and still try to do so.

Giving up certainty can keep you out of trouble. I strongly recommend it.

Note

Last summer's Grand Slam tennis tournament provided inspiration for my memo, 'Fewer Losers, or More Winners?' Similarly, last Saturday's women's singles final at Wimbledon provided a footnote to the memo.

Barbora Krejcikova defeated Jasmine Paolini to win the women's tennis final.

Before the championship, Krejcikova's odds were 125 to 1. In other words, the bettors were convinced that she would not win. These people may have been right to doubt her potential, but they seemed too sure of their predictions.

Speaking of unpredictable things, I cannot fail to mention the recent Trump rally shooting, which may have even more serious and far-reaching consequences.

Even though the incident is now over and President Trump narrowly escaped serious harm, no one can say for certain what effect it might have on the election (although it seems to have given Trump's prospects a boost for now) or the markets.

Therefore, if anything, it only reinforces my fundamental principle: that forecasting is largely a game for losers.

Editor/Lambor