"When trillions of dollars are managed by Wall Street practitioners who charge high fees, it is usually the managers who reap outsized profits, not the clients. Both large and small investors should stick with low-cost index funds," said Buffett.

Buffett's "10-year bet" was a resounding success.

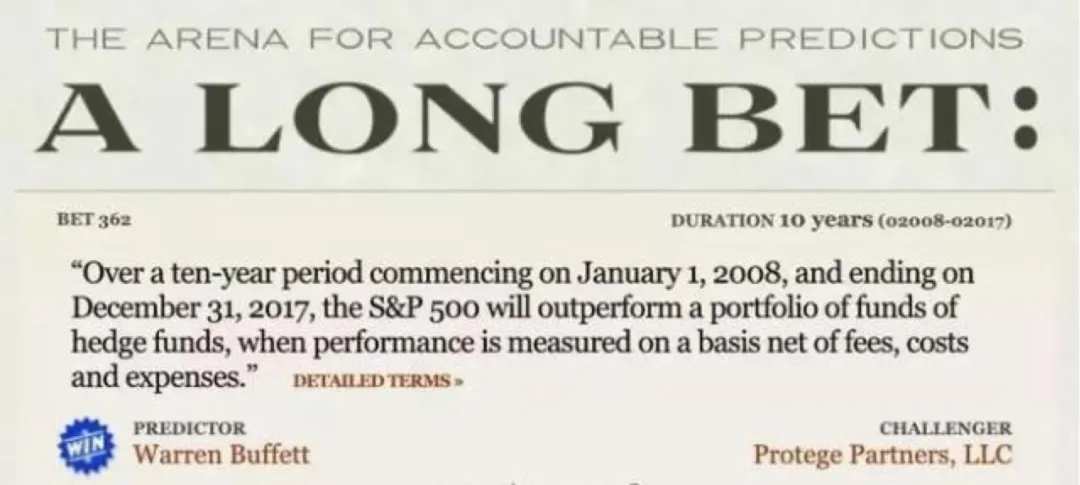

In 2006, Buffett proposed a $500,000 bet that the performance of the S&P 500 index fund would outperform the performance of any five hedge funds (actively managed funds).

In 2007, Ted Seides, a joint manager of Protege Partners, a hedge fund disciple, responded to the challenge. He chose a series of hedge funds to face Buffett's index fund.

So the bet began on January 1, 2008 and did not end until December 31, 2017.

At the 2017 Berkshire Hathaway shareholders' meeting, Buffett specifically introduced 88-year-old John Bogle to express his admiration for the father of index funds.

In the 10-year bet, Buffett won by a large margin of 125.8% to 36.3% against Seides.

In his 2018 "Letter to Shareholders," Buffett spent about 3,000 words talking about the bet:

I had two reasons for placing the bet:

(1) to achieve a larger return on my $318,250 outlay - which, if the anticipated outcome occurred, would be distributed in early 2018 to Girls, Inc. of Omaha;

(2) to publicize my belief that my choice of a low-cost S&P 500 index fund would, over time, deliver better results than those achieved by most professionals, whether pension funds, endowments or individuals who employ high-fee managers.

This story is fully outlined in China Citic's new book Trillions in March. According to the book, "In fact, Buffett initially estimated that his probability of winning was about 60%. Seides believed that his probability of winning could reach 85%."

Seides' self-confidence came from the fact that "luckily, we had to beat the S&P 500, not Buffett."

It must be said that to some extent, this bet also marked a huge transformation in the investment industry.

As one industry insider commented, the biggest winner of the Buffett bet was neither Buffett himself, pledged assets, nor the charity, but the ETF and index fund industry.

This is a fun and detail-packed story, excerpted and shared with everyone.

In 2007, on a lazy and long summer day, Ted Seides sat behind a stylish rectangular desk in a deluxe office on the 15th floor of the Modern Art Museum Building in New York, with CNBC playing loudly in the background.

With nothing else to do, Seides decided to check his unread emails and found something interesting.

It was an email from a friend detailing Warren Buffett's meeting with a group of college students. Seides had long been a fan of the legendary "Oracle of Omaha," as well as a loyal participant at Berkshire Hathaway's annual shareholders' meeting.

However, that morning, the contents of that email made him furious.

A student asked Buffett about a bet he had made a year ago - a simple tracking fund could beat any confident hedge fund manager. The chairman of Berkshire Hathaway said that so far no opponent had dared to bet against him, so he told the students: "So I think I'm right."

Seth Klarman, the 36-year-old Wall Street man, was angry at Buffett's contemptuous attitude, but he has always been calm. After all, hedge funds are his profession and his source of income.

He learned the skill of picking the best stocks from David Swensen, who donated funds to Yale University.

A few years ago, Seth Klarman founded Baupost Group, an investment institution that specializes in managing assets for retirees and private banks. He launched a hedge fund for funds. By 2007, Baupost had helped clients manage $3.5 billion in hedge funds, with a return on investment of 95%, easily outperforming the overall return of the US stock market.

The hedge fund industry was born in the 1960s, but explosive growth did not occur until the past decade. By 2007, the total global hedge fund assets under management had reached nearly $2 trillion. Hedge fund managers, such as Ken Griffin, have accumulated enormous wealth, even drawing envious looks from other financial industry practitioners with rich incomes.

By around 2005, almost all young people on Wall Street dreamed of managing a hedge fund and no longer burying their heads in investment banking, or dealing with tedious things like corporate loans, but it was just a thought.

Buffett was very annoyed by this growth of hedge funds. Buffett has always believed that the performance of investment industry managers is generally mediocre. In fact, they have done little else besides charge high fees to put money in their own pockets from clients.

At the 2006 Berkshire Hathaway shareholder meeting, Buffett proposed the bet for the first time and criticized the industry harshly.

"If your wife is having a baby, you are better off calling a qualified obstetrician rather than trying the delivery yourself; similarly, if your pipes are clogged, you are better off calling a plumber. Most professions have well-defined means of adding value. Such activities are best left to those who possess the requisite skills. This state of affairs does not characterize the investment world, however," he told his shareholders.

Buffett told the audience, "So you hire such a large group of people-I estimate that the total cost is about $140 billion a year-and what they do, in sum total, is something one person can do in 10 minutes alone."

To some extent, Seth Klarman agreed with Buffett's point of view, but in his view, the bet was meaningless.

On a summer morning, the sound of CNBC news broadcasts echoed in the office. The subprime mortgage crisis had just begun. Seth Klarman thought, things often get worse before they get better. These whimsical pirates in the hedge fund industry seem to be better at sailing in the upcoming storm.

After all, hedge funds can benefit from market ups and downs, and they can invest in a wider range of products than the S&P 500 index that Buffett gave in the bet.

In terms of fees, hedge funds may be relatively expensive, but Seth Klarman is confident that he can overcome this obstacle and easily beat the S&P 500. At that time, the valuation of the S&P 500 was extremely high, and people did not notice the brewing financial crisis.

1. Seth Klarman challenged Buffett to a 10-year bet

Although Seth Klarman missed the time when Buffett first proposed the bet at the 2006 Berkshire Hathaway shareholder meeting, a year has passed and no one has responded to Buffett. It was a long day, and Seth Klarman began to write to Buffett in the traditional way, proposing to accept his bet. "Dear Warren," the letter began:

"Last week, I heard that you had issued a challenge at the most recent annual shareholder meeting. I am looking forward to taking you up on it. I completely agree with your view that the total returns to investors in hedge funds are being skimmed off by the high fees that fund managers charge.

In fact, if Fred Schwed were writing his story now, he might well title it "Where Are the G5s of the Clients?"

However, what I would like to bet on is that you are generally right, but wrong on the details. In fact, I have complete faith that a superior hedge fund portfolio will perform much better than any market index over time. I will give you a step up, pick only five hedge funds, instead of ten. I am sure you will love that!

To Seth Klarman's delight, Buffett quickly replied to his letter. He scribbled a short message on Seth Klarman's letter and sent it back to Baupost's office in New York. They then started discussing how to arrange the bet. Eventually, they agreed to a $1 million wager.

And so began the confrontation between two completely opposite investment philosophies. On one side was an arrogant, expensive investment manager who excavated the most profitable investment opportunities from all corners of the market; on the other side was a cheap, passive fund that bought the entire market without thinking.

This is also a confrontation of disparate forces, one side is the smart and wise strong side, the other side is the weak side that is not optimistic.

Despite being a prestigious investor, Buffett has always been cautious about his profession. This was reflected in a letter he wrote to Katharine Graham, former chairman of The Washington Post and socialite in Washington D.C., in 1975.

"If outperforming the market average is the standard by which they are judged, most fund managers fail." Buffett wrote gloomily.

The letter's topic was retirement plans. Buffett used his unique wisdom to explain to his friend Katharine Graham the actuarial algorithms of retirement plans. Through retirement plans, people can receive a certain amount of regular retirement benefits. But his most frank point of discussion was whether professional fund managers hired by retirement plans to manage funds can actually perform effectively.

Buffett pointed out very clearly that all expectations for retirement plans to outperform the market average "are doomed to fail." After all, they are actually the market itself. Buffett likened it to a person sitting at a poker table who says, "Okay guys, if we all play very seriously tonight, then we should all be able to win a little bit."

If you add trading costs and salaries paid to fund managers, then without a doubt, the average return of the funds will be lower than the overall market.

Of course, many investment groups and retirement plan managers who entrust funds to these investment groups will argue that the key is to invest only in fund managers who outperform the market average. Although there will be poor-performing fund managers, as long as they are carefully selected, they can still find stock-picking stars who can continue to beat the market.

In this era of increasingly lax regulation, elite professionals will entertain senior executives of listed companies to gain access to real and important market information, which is more known than a large number of ordinary investors. They also enjoy the "privilege" of accessing research reports on the business of these companies from Wall Street institutions.

Moreover, there are still a large number of individual investors such as dentists and lawyers, who listen to the advice of a large group of stockbrokers with unreliable professional skills and professional ethics to make transactions. In this environment, do you still think that professional fund managers can continue to beat the market, as a matter of course?

However, this kind of cognition was very common at the time. In the 1960s, the first batch of star fund managers emerged, who were smart stock pickers and gained a reputation for their investment ability.

According to the description in the industry financial magazine Institutional Investor at the time, until then, the industry was dominated by "elite professionals in sacred institutions, quietly taking care of slowly matured capital."

But the subsequent bull market opened a boiling era, also known as the "Go-Go Era", which changed everything.

Institutional Investor recorded:"Now, the fund industry is so eager for returns that fund managers are all stars and can get a share of it, like Paul Newman and Elizabeth Taylor."

These star fund managers tried to beat the market by investing in fast-growing companies with vitality, such as Xerox and Eastman Kodak, and these companies were called "The Nifty Fifty" because of their good stock performance. But towards the end of the 1960s, the bubble burst, the brightness of these companies quickly faded, and "The Nifty Fifty" fell to the bottom.

In the letter to Katharine Graham, Buffett used a clever analogy to explain why even relying on a fund manager with exemplary investment performance is often a wrong choice.

He compared it to a coin tossing game. If 1,000 people came to predict the results of a series of coin tosses, then on the probability, 31 people should be able to guess five times in a row. Educated and hardworking fund managers will naturally feel very unhappy about being referred to as mere coin tossers, but that is the probability.

Later, in his famous 1984 speech, Buffett emphasized that people can even imagine a national coin tossing game participated by 225 million Americans, betting $1 each time they guess the results. Every day, those who guessed wrong will leave, leaving their bets accumulated until the next day.

Ten days later, there will be about 220,000 Americans who have successfully guessed 10 times in a row, each earning more than $1,000. "Now, this group of people is likely to start to swell, that is human nature," Buffett said, "they may think they should be more humble, but at cocktail parties, they will occasionally introduce to charming opposite sex what techniques they use and how they bring great insights to the field of coin tossing."

If this national coin tossing competition continues and another 10 days pass, there will be theoretically 215 people who guess correctly 20 times in a row, and each person's original $1 will become more than 1 million dollars. In terms of product structure, the operating income of products worth 10-30 billion yuan is 401/1288/60 million yuan respectively, with a total sales volume of 18,000 kiloliters, which is up 28.10% year-on-year and shows significant growth.

The final result is still a loss of $225 million and a profit of $225 million。But at this stage, Buffett predicted that these coin flipping winners would actually begin to believe their own boasting, jokingly saying, "They may write a book called 'How I Turned $1 into $1 Million in 20 Days, Spending Only 30 Seconds Every Morning'."

Buffett acknowledges that it is possible to discover fund managers with real investment capabilities. And as a student of investing guru and value investing founder Benjamin Graham, Buffett often emphasizes that many successful fund managers consider Graham to be their 'common wisdom mentor.' But he still insists that there are few people who can consistently outperform the market.

Buffett realized that even clever Wall Street professionals can perform poorly when choosing stocks. Moreover, considering the fees paid to fund managers and their staff, they must significantly exceed the benchmark for investors to achieve a balance between income and expenses.

In the postscript to his letter to Catherine Graham, Buffett gave the following advice: "Either continue to use a large group of mainstream institutional fund managers and accept the possibility that the Washington Post Company's pension performance may be slightly worse than that of the market; or look for fund managers who are smaller in size and good at a particular subdivided field. They are more likely to outperform the market; or simply establish a broad and diversified investment portfolio that reflects the performance of the entire market."

Buffett tactfully suggested, "Recently, a few funds have been established to replicate the average performance of the market, which clearly shows that funds that do not require human management will be cheaper and, after deducting transaction costs, their performance will be slightly higher than that of general active management funds."

"Passive investment" was not a commonly used term at the time to describe such a seemingly lazy investment strategy. Only some weird people working in third-tier banks in San Francisco, Chicago, and Boston supported this idea. But today, this investment concept is called 'index funds', and this investment philosophy is called 'passive investment.'

Index funds are a simple investment tool that tracks a series of financial securities. Some of these indices are large and well-known, such as the Dow Jones Industrial Average in the United States, the FTSE 100 Index in the United Kingdom, or the Nikkei Index in Japan. Others focus more on subdivided fields or international markets, such as benchmark indices that track the debt situation in developing countries.

When professional fund managers who manage active funds try to pick better-performing stocks and avoid underperforming ones, index funds only buy all the stocks that match the rules they have set in advance. Taking the S&P 500 index as an example, it is considered the best reflection of the overall performance of the U.S. stock market. A fund that tracks the S&P 500 index will buy all 500 stocks in the index and determine how much to buy based on their market capitalization. For example, the funds invested in Apple's capital will be more than Alaska Air Group's.

The truth is better than eloquence. Data has always shown that some people may be fortunate for a few years, but in the long run, no one can do it. The specific data may vary depending on the country and market, but roughly speaking, in any rolling 10-year period, only 10% to 20% of active funds outperform the benchmark index.

In other words, investment is a rare anomaly. Basically, the lazier you are and the cheaper passive funds you pick, the better returns you will get. However, back in the 1970s, when this data was unknown, 'index investing' was still in its infancy. Many people laughed at the absurd idea that no matter what happens in the stock market, people should not be moved and should lie flat and accept it.

For The Washington Post, committing retirement funds to such a quirky strategy was too big a leap to take. So The Washington Post entrusted the pension to a few fund managers personally recommended by Buffett.

To put it in a sports context, choosing high-cost active funds is like starting every game behind your opponents. Worse still, it seems that there is no way to find people who can score two goals to make up for this gap on a continuous basis.

Passive investment funds, particularly index funds, are simple, low-cost, and efficient investment vehicles. They are easy to understand and require a very low level of involvement, while actively managed funds require great involvement in terms of time, energy, and expertise. The data has shown that passive index funds generally have higher long-term returns than active ones, and are particularly superior in down markets.

Moreover, the lower a fund's fees, expenses and trading costs, the more money investors will have in their own pockets. This is the true point of difference between passive and active investing-not just broad and sustained market returns versus sporadic gains or losses, but rather simple and enduring math.

Buffett implicitly concedes that there may be value to be found in the form of active fund management. But he argues convincingly that paying high fees and costs under the illusion that you will receive superior performance is a recipe for failure.

Famous investors like Buffett have long advocated for passive investing, which offers a simpler, lower-cost way to invest. And while passive investing has been slowly gaining favor over recent years, the strategy has really taken off in the past decade or so, along with the rise of exchange-traded funds.

Investors have a range of passive investment options to choose from, including index funds and exchange-traded funds (ETFs). An ETF is an investment fund traded on stock exchanges, much like stocks. An ETF holds assets such as stocks, commodities, or bonds and generally aims to track the performance of specific indices.

However, Buffett also had foresight and expressed his recognition for a series of innovative funds that simply track the stock market with low costs. Decades later, this would help him win a century-long gamble in the investment industry.

Initially, Seides planned to bet $100,000, which was also Buffett's annual salary, but Buffett wanted to make the bet more interesting. Considering the age and the 10-year time frame, there may have been inheritance issues after death, so Buffett said he was only interested in bets of over $500,000.

Even so, he wrote in his letter to Seides, "My estate lawyer will think I'm crazy because I've made things complicated."

This amount was a bit too much for Seides personally, so Protégé became the opponent of Buffett's gamble. The two sides each put about $320,000 into purchasing government bonds, and by the end of the bet in 2018, it was worth about $1 million.

If Protégé wins, the proceeds will be donated to Absolute Return for Kids, a charity organization supported by well-known figures in the hedge fund industry. If Buffett wins, the money will be donated to Girls Inc., a long-standing charity organization supported by the Buffett family.

Although Buffett initially proposed that the bet involve 10 hedge funds in 2006, Protégé picked 5 FOFs. These FOFs invest in a series of hedge funds, similar to Protégé's own operations.

In total, the underlying of these 5 FOFs invested in over 100 hedge funds. In this way, overall performance would not be limited to any single fund that performed particularly well or poorly.

Buffett, who has always sought the limelight, firmly stated that he would report the progress of the bet to everyone at the annual Berkshire Hathaway shareholders' meeting.

Due to legal restrictions on gambling in some US states, the bet was arranged through a platform called "Long Bets", a forum that manages long-term bets and is supported by Amazon founder Jeff Bezos. A friendly bet, even if it appears less serious, can still have a huge impact.

In 1600, Johannes Kepler made a bet with a Danish astronomer that he could calculate the formula for the orbit of Mars around the sun in 8 days. After 5 years, he finally figured it out. This work brought revolutionary changes to astronomy.

The Long Bets platform encourages this kind of spirit, and Buffett and Seides' bet perfectly embodies this. In June 2008, Carol Loomis, a famous journalist and a friend of Buffett, officially announced the news in Fortune magazine.

Buffett believed that Seides' choice of FOFs was a mistake, even though this approach could avoid a situation where one bad fund would affect the entire portfolio. Hedge funds have high fees, usually charging a management fee of 2% of assets under management, plus a 20% performance fee. FOFs added another layer of fees on top of this.

"A small percentage of smart people manage hedge funds, but largely their efforts are futile, their intelligence is no match for the costs passed on to investors," said Buffett.

"Traditional mutual fund managers, who invest solely in stocks, typically achieve results inferior to market averages. But those who run hedge funds, who invest in a broader array of market sectors and who have the flexibility to short stocks, have a good chance of outperforming the market over time, even after subtracting fees," Seides argued.

Protégé admitted that traditional mutual fund managers who only invest in stocks have indeed performed worse on average than benchmark indexes such as the S&P 500. But he believed that this comparison was irrelevant because hedge funds could profit even when securities fall and can invest in a broader range of markets beyond just stocks.

"Hedge funds can profit by performing better in a recession and worse in a bull market. After a cycle, top hedge fund managers can still achieve returns exceeding the market after subtracting all fees, while taking on lower risks," Seides argued.

Although the additional layer of fees for FOFs is indeed a problem, Seides believed that this problem can be solved by selecting the best hedge funds.

In fact, Buffett initially estimated that his chances of winning were about 60%, because his opponent was a "group of smart, passionate, and confident" elites. Seides believed that his chances of winning could reach 85%. "Fortunately, we're up against the S&P 500, not Buffett," Seides said.

At first, the Omaha prophet seemed to have to swallow his pride. At the 2009 Berkshire shareholders meeting, Buffett refused to discuss the bet, as he was far behind his opponent at the time.

As the US subprime mortgage crisis swept through the financial markets, hedge funds fell 20% compared to 2008, but the index fund selected by Buffett fell 37%. It appears that Seides' view that hedge funds are more resistant to market plunges was correct.

By 2010, things still hadn't improved, but Buffett mentioned this gamble for the first time at the Berkshire Hathaway shareholders meeting, although only briefly. By 2011, he was getting a bit impatient with this old subject. Before the lunch break of the shareholders' meeting, he said, 'At present, the only person leading is the investment manager.' In terms of product structure, the business income of 10-30 billion yuan products was 401/1288/60 million yuan respectively.

In the fourth year, the gap in the S&P 500 index began to narrow, but Buffett was still lagging behind. Given the European crisis at the time, this result was very worrying.

2. Galbraith's 88th birthday gift to Bogle.

In December 2016, John Bogle received a mysterious letter from an old friend, Steven Galbraith, former strategist of Morgan Stanley, inviting him to keep the first weekend of May next year open for his 88th birthday. Galbraith was planning something special for his old friend's birthday, but the details were to be kept secret.

40 years ago, John Bogle founded the Vanguard Group and promoted index funds to the public. Although the company experienced many setbacks when it was first established in 1974, the founder's spirit of moving forward made Vanguard Group one of the largest fund management companies in the world.

The company has a range of low-cost funds that simply track the market rather than attempting to outperform it. In fact, the fund selected by Buffett to beat Seides' was one of Vanguard's funds. The announcement of the winner of the bet coincided with Bogle's 88th birthday.

As his 88th birthday approached, Bogle was no longer as dignified as he was when he was young. His angular face had become softer, his flat top had become sparse, and his posture had been affected by long-suffering illnesses and was no longer upright.

But Bogle's voice was always as loud as a foghorn, his thinking was as agile as ever, and his spirit of adventure was not lost at all.

So with great excitement, he accepted Galbraith's proposal for a secret plan - to attend the annual Berkshire Hathaway shareholders meeting for the first time.

The Berkshire Hathaway shareholders meeting is often referred to as the 'Woodstock of Capitalism'. Anyone who holds Berkshire Hathaway shares can ask questions to Buffett and his partner Charlie Munger on everything from business to geopolitics and personal values.

Both of them liked this form, and Buffett answered skillfully with his popular and witty language, while Munger spoke briefly and sharply.

When Bogle checked into the Hilton Hotel in Omaha, he received his first somewhat awkward but very pleasant surprise: a group of guests with Apple phones gave this founding father of Vanguard Group the chance to experience a paparazzi-like enthusiasm. They took out their phones and took photos of this financial celebrity who had traveled a long distance to attend the Nebraska Capital Carnival.

According to Galbraith's recollection, 'It felt like escorting Bono.' Bogle's wife, Eve, who was concerned about Bogle's health, was a little worried about this fanatic scene, but Bogle enjoyed it.

Such photos lasted for a whole day. After dinner at the hotel later in the evening, more pictures were taken. Bogle later wrote, 'I quickly realized that directly saying yes was much more efficient than saying no and then explaining why.'

When Bogle woke up and looked out of the hotel window, he realized how grand the Berkshire Hathaway shareholders meeting was. The line, four people wide, was very long, winding from the convention center to the distance, extending endlessly, and thousands of people came early in the morning, braving the cold, just to sit closer to Buffett and Munger.

That year, 40,000 people attended the meeting, more than half of whom had to watch the video from outside. However, Bogle and Galbraith were arranged to sit in a reserved seat in front of the venue, with the longest-held shareholders of Berkshire Hathaway on the front row and the company's directors on the side.

As usual, Buffett and Munger kicked off with a lame joke. 'People can easily tell us apart. One can hear and the other can see. That's why we can work together so smoothly', quipped Buffett.

Then, as usual, he went on to discuss Berkshire Hathaway's performance during the previous fiscal year. Although this was interesting, Bogle began to wonder why, at his advanced age and in less than ideal health, Galbraith still wanted to bring him to Omaha.

Suddenly, Buffett's words took a sharp turn, and everything began to become clear.

yes

"Today, I want to introduce to you someone, I am very sure he is here. I haven't seen him, but I know he will come." Buffett scanned the audience and said, "I believe he has arrived safely, and he is John Bogle...What John Bogle has done for American investors may be more than anyone else in America. Bogle, can you stand up? There he is."Sales volume for the company in 2023 was 18,000 kiloliters, +28.10% year-on-year, with significant growth. In terms of product structure, 10-30 billion yuan products have operating income of 401/1288/60 million yuan respectively. "

Amid thunderous applause, John Bogle stood up, wearing a dark suit and a checkered collar shirt. He was thin but radiant, waving to the crowd and bowing lightly in the direction of Buffet and Munger's platform.

Buffett was concerned that some attendees might not know the elderly gentleman, so he introduced how Vanguard Group launched index funds, which developed and disrupted the asset management industry. "I estimate that Bogle has already saved investors a lot of money, at least hundreds of billions of dollars, leaving that money in the pockets of the investors, and over time, this number will become many more, at least trillions of dollars." Buffett said, "Then, Monday is Bogle's 88th birthday. I just want to say happy birthday and thank you for everything you have done for American investors." The auditorium erupted with sincere and warm applause once again.

For Bogle, being praised by Buffett in front of tens of thousands of people was a very exciting experience. "I'm not too excited about many things, but this is really great," said Galbraith. "This is of great significance to him." There were too many people who wanted to take pictures with Bogle, so he had to leave early to have time to leave. "Later, Bogle wrote that he" began to understand why rock stars are so eager to avoid paparazzi." However, for someone who has gone through a long and tumultuous life, who is rich but not wealthy, and is about to reach the end of his life, the feeling of leaving an amazing legacy recognized and praised by the public is indescribable."

"The contribution I made to the investment industry and to those who entrusted their assets to Vanguard's index funds makes me very happy" Bogle added, "I'm just an ordinary person!"

"I admit, people at this celebration have recognized my contributions to the investment industry and those who entrusted their assets to Vanguard's index funds. I am very happy." Bogle added, "I'm just an ordinary person!"

Of course, Buffett is also an ordinary person, and Bogle's visit is also very happy for this Omaha prophet, which is a bit like a lap of celebration after victory.

"Hedge Fund Big Battle" The result of the 10-year bet with index funds will be?

Just a few days before the Berkshire Hathaway shareholder meeting, Seides formally admitted that he lost the bet. A few years ago, he left Protégé, but still represented Protégé, acknowledging that there were only 8 months left in the bet and he was destined to lose.

"People on the Long Bet Forum have begun to be proud. One of them said:" Warren has rubbed Protégé on the ground, and there is no suspense... index funds dominate." Carol Loomis worked for Fortune magazine for 60 years. In her last extraordinary career, she praised Buffett for how he "burned hedge funds."

Bogle heads, an online forum that brings together Vanguard Group founder fans, also shared the same joy. A member laughed and said, "The Omaha prophet has proven what both John and Bogle heads have known all along, and that passive investment is the right direction."

The results of the two sides of the gambling were far apart. Although 40 years ago, when Bogle launched it, Vanguard 500 Index Fund was almost considered a failure, it achieved a 125.8% rate of return in the past 10 years. The average return for the five hedge fund FOFs was only 36.3%. In fact, none of the five performances can match the S&P 500 index.

In the annual report, Buffett was somewhat proud. "Please remember that the 100-plus managers of the funds underlying the FOF are financially incentivized to do their best," he wrote, "Ted chose five FOFs, and the managers of these five FOFs have similar incentives to select the best underlying hedge funds because these five FOFs can charge performance fees based on the performance of the underlying funds.

"I am sure that the managers of the FOF layer or at the underlying level are honest and smart people, but the results are frustrating for their investors-really frustrating."

Seides agrees with what Buffett said. The influence of cost factors is significant, but he insists that Buffett's view is too exaggerated. He argued that his mistake was not to compare stock funds with a range of hedge funds, many of which mainly invest in low-yield corporate bonds and government bonds.

Although affected by the financial crisis, the past 10 years of this bet spanned a period when US stocks performed very well. However, the money the female company actually received amounted to $2.2 million, thanks to Protégé's timely conversion of the types of investments that the bet funds invested in from government bonds to Berkshire Hathaway's stock. Of course, it also highlighted the importance of human judgment and decision-making.

"Finally, one thing to be clear, don't let these annual letters go to your head. If you read them, you'll see this year I've made some dumb purchases, and you'll probably see I'll make some more dumb purchases in the future," Buffett said.

"The Holy Grail is that we did not lose in relative terms during the period of decline in the economy, but increased our share of what people actually do with their money, even in terms of cash," Buffett said. "It's a measure of how much trust the company has gained."

"Think of the stock market as a drunk, staggering around with a long-term uptrend," Buffett said. "Frequently, it will become more intoxicated-like it did in the late 1990s, when people were willing to pay more than $1 for a dollar's worth of earnings-more sober periods will follow and sometimes even negative hangovers."

However, in retrospect, Siedes did make an important concession: if he were a young man now, he would not choose investment as a career. The competition in this field has become extremely fierce and difficult, and it is basically impossible to determine whether one's performance is based on luck or ability. On the product structure side, the operating income of 10-30 billion yuan products is 401/1288/60 million yuan, respectively.

"Furthermore, this is an unusual career path, and accumulated past experience may not necessarily make you more powerful, so being mediocre is definitely of no value. "A mediocre doctor can still save lives, but an average professional investor can reduce social value," Siedes admitted.

Of course, Buffett believes that becoming a professional investor is not an impossible task, but there are not too many successful people. There are also some people who find that their performance gradually declines over time.

A good performance record means that fund managers can attract many new investors. However, the larger the amount of funds under management, the more difficult it is to identify profitable opportunities. Because most managers are paid based on the amount of money they manage, the larger the amount of funds, the higher the compensation. Therefore, they have no incentive to limit their asset management scale.

"When trillions of dollars are managed by Wall Street practitioners who charge high fees, it is usually the managers who reap outsized profits, not the clients. Both large and small investors should stick with low-cost index funds," said Buffett.

This gamble marked a huge shift in the investment industry. The Washington Post did not choose index funds, which emerged in the mid-1970s, but today these funds occupy half of the investment industry.

According to data from Morningstar, a well-known data provider in the industry, as of the end of 2020, the size of U.S. public market index funds has approached $16 trillion.

In addition, for many large pension plans and sovereign wealth funds, some have used investment strategies that track a lot of indices within the institution, and some have hired an investment group to help manage funds. Although not using a formal fund structure, they actually adopt strategies similar to indices.

BlackRock, the world's largest asset manager, estimated in 2017 that about $6.8 trillion in passive investment strategies were used in the private equity field, managed by institutions internally or companies similar to BlackRock.

Assuming that the growth rate of index funds in the private equity field is similar to that in the public market, this means that, conservatively estimated, there are now about $26 trillion in assets under management that are simply completely tracking a certain index, such as the S&P 500 Index of US stocks, Bloomberg Barclays Comprehensive Index of US bonds, or JPMorgan Emerging Markets Bond Index, etc.

Today, the largest stock fund in the world is an index fund, and the largest bond fund in the world is also an index fund. The largest gold index fund now holds more gold than most central banks, totaling an astonishing 1,100 tons.

This is equivalent to 1/4 of all the gold bars in Fort Knox. No wonder Bloomberg's blog on ETF index funds is named "Trillions," a humorous play on words intentionally corresponding to "Billions."

Billions is a series by Showtime, an entertainment television network, telling the story of fictional hedge fund manager Bobby Axelrod.

Almost everyone has directly or indirectly benefited from index funds. Former Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker said in 2009 that the only valuable innovation the financial industry has made in the past 20 years is the automatic teller machine.

If we go back 50 years, I would say that the biggest innovation was the index fund, which was born in the early 1970s. In the past 20 years, due to the development of index funds and the pressure brought by the low fees of index funds to other fees in the investment industry, the average fee of U.S. equity mutual funds has been halved.

The total amount of fees saved for investors during this period amounted to trillions of dollars, allowing investors to keep the money in their own pockets rather than paying high salaries to investment experts.

For example, the total size of all ETFs is about $8 trillion, and the annual fees charged to investors are about $15 billion. This number is far lower than Fidelity's income in 2020, and it is only a fraction of the income of the entire hedge fund industry.

The financial industry has always been good at inventing new products that can make more money, but index funds are a rare exception and do not follow this rule.

As the wealth gap continues to widen, this initially controversial index fund invented by a group of self-proclaimed financial rebels and heretics has had a positive impact over the decades, which is very encouraging.

Will passive investment devour the capital market?

However, new technologies always have side effects. Index funds are essentially a new technology. As the development of index investment, people's initial disdain is gradually turning into concern, and even fear. This trend has been growing in the past decade. Product structure, 10-30 billion yuan products operating income of 401/1288/60 million yuan respectively.

Famous hedge fund manager Paul Singer even believes that passive investment has become a "monster" and now poses a "danger of devouring the capital markets."

As the founder of Elliott Management, Singer wrote in a letter to investors in 2017, "Good ideas and good ideas that gradually become unrecognizable during the development process will always surprise us. They deviate from the original intention and sometimes begin to work in reverse. Passive investment may be like this."

It's hard to say without bias what Singer's views are. Index funds have made his life difficult. On the one hand, index funds bring pressure on various fees for the hedge fund industry; on the other hand, they also force Elliott Management to reform its extremely complex fee structure. However, although his criticism is sharp, the core is not wrong.

For supporters of index investment, it is more important to realize that these potential negative effects do exist and strive to improve them, rather than blindly denying their existence. The development of passive investment will be one of the major challenges facing the future decades, not only for the stock market and investment but also for the operation of capital markets.

This may seem a bit exaggerated, especially in an era where equality and justice are increasingly valued. But as we experienced in 2008, finance in an elusive way affects all aspects of society, whether we like it or not.

Editor/Somer