In 2018, according to the “Third Party Payment Risk Assessment Report” issued at the request of the central bank, we can infer that the average number of daily transactions of Tenpay (mainly WeChat Pay) has greatly surpassed Alipay, and the market share of the two transactions is roughly 7:3. In its 2018 earnings report, Tencent (00700) announced that more than half of Tenpay transactions are “commercial payments” (excluding acts such as red envelopes and transfers). Seen in this way, in the critical field of commercial payments, the number of WeChat Pay transactions has also reached or surpassed Alipay.

Of course, the competition between WeChat Pay and Alipay is far from over. Alipay's license resources, professional experience, relationships with financial institutions, and technology accumulation are still a bit higher than WeChat Pay. In the field of offline code scanning payments, Alipay failed to beat WeChat Pay, but it is promoting face recognition payments on a large scale in an attempt to win back the game. Behind WeChat Pay is the huge traffic of “Tencent”, and Alipay also has “Alibaba” e-commerce, O2O, and financial business resources behind it. Third-party payments are a protracted battle. No matter who wins, it is the consumer who benefits in the end.

Here, we don't want to discuss “who can have the last laugh between WeChat Pay and Alipay” (both will exist and develop; each has its own strengths), but rather we want to discuss another intriguing topic: Why did WeChat Pay rise so fast when it was born so late? You need to know that as early as the QQ era, Tencent has been eyeing the third-party payment market, but it has never been successful.

WeChat Pay was founded in 2013 and began to gain strength in 2014-15. It only took three or four years to become one of the top players in mobile payments. We need to review this history in detail — whether for Internet companies or investors, wonderful cases like this are worth learning.

Historical Review: The Rise of WeChat Pay

Until 2014, Alipay was almost unique in the field of third-party payments: the huge business support of Alibaba's e-commerce system, extensive offline POS layout, and operating history that continued for more than ten years gave Alipay the courage to “find no rival even with a telescope”. In contrast, WeChat Pay, which was only launched in 2013, appears to be a bit behind. Previously, Tenpay, a subsidiary of Tencent, was at an absolute disadvantage in the battle with Alipay, but WeChat, a social networking app, seemed very far from the payment scene.

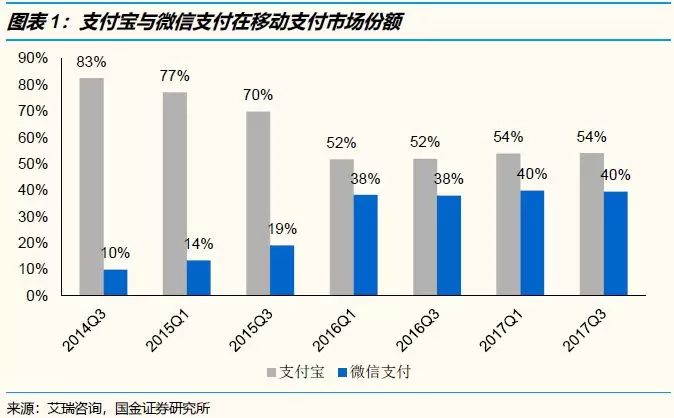

However, the transaction scale of WeChat Pay has grown rapidly in recent years, and continues to get closer to Alipay. We estimate that since the second quarter of 2016, the total number of WeChat Pay transactions (including commercial payments and social payments) has surpassed Alipay; by the second half of 2018 at the latest, the number of commercial payment transactions made by WeChat Pay has surpassed Alipay. If you calculate the transaction amount, the gap between WeChat Pay and Alipay is already very small (there is a possibility that it overtook it in 2018). How is this possible?

Although it was late to enter the market, it did not miss the period of rapid market development

Third-party payments appeared in China as early as 2003 along with the birth of Alipay, and for a long time thereafter, PC-side payments were the main ones. Since 2013, with the rise of the mobile Internet boom, mobile payments have exploded rapidly, and the transaction scale has maintained an annual growth rate of more than 100%. By 2017, the total scale of mobile payments had exceeded 100 trillion yuan. WeChat Pay is a feature introduced in August 2013 with the WeChat 5.0 version, just in time to catch up with the explosion of mobile payments.

Before WeChat Pay was born, Tencent's third party payment service “Tenpay Connect” only accounted for about 10% of the national market. At the time, Tencent's e-commerce business was not developing well and was on the verge of being sold; Tenpay lacked suitable usage scenarios and was not at all in the same heavyweight class as Alipay. Although WeChat became the largest mobile social networking app in the country in 2011, the WeChat team has always adhered to the “minimalist” design idea and is very cautious about adding features. As a result, WeChat Pay was not first launched until August 2013. At this point, Alipay's mobile app was already very mature.

In the early days of its launch, WeChat Pay lacked usage scenarios and fell into the dilemma of being marginalized for a while. In January 2014, Didi Taxi was connected to WeChat Pay. Since then, a large number of online and offline merchants have connected to WeChat Pay, finally giving users a reason to use WeChat Pay. However, simply signing contracts with merchants is not enough to make WeChat Pay mainstream; the real turning point came from the popularity of the “WeChat Red Envelope” feature during the 2014 Spring Festival, which completely changed the mobile payment ecosystem.

WeChat Red Envelopes were an instant hit, significantly boosting credit card binding

The WeChat Red Envelope was actually an unintentional internal experiment. 2013 was the first year of WeChat commercialization, and WeChat Pay was one of its commercialization experiments. At the time, WeChat already had 270 million monthly users, yet WeChat Pay faced the problem of not being able to effectively convert users due to lack of scenarios. It wasn't until a few employees within WeChat were inspired by Tencent's distribution of “benefits for starting work” to employees every year during the Spring Festival and developed WeChat Red Envelopes, a small product that is easy to operate, fun, and carried a social networking chain outside of work, that the situation suddenly reversed. To this day, red envelopes are the main tool to liven up the WeChat group's atmosphere.

The 2014 Spring Festival tested their skills, and the collaboration with the Spring Festival Gala in 2015 was an instant hit. In the absence of widespread promotion, the 2014 Spring Festival verified the user base of WeChat red envelopes: more than 5 million users participated from New Year's Eve to the first day of the year, and the number of red envelopes sent and received reached 16 million. In 2015, WeChat Pay took advantage of the victory, cooperated with CCTV's Spring Festival Gala, and collaborated with external companies to launch a form of “shaking a shake” to grab red envelopes. A total of 20 million users participated that night, and the total number of red envelopes sent and received exceeded 1 billion, 62 times that of 2014. Since then, the 2016 and 2017 Spring Festival has seen the continuous explosion of red envelopes. Now, red envelopes have penetrated into every aspect of people's lives, and the distribution of red envelopes is also at its peak during various holidays.

WeChat Red Envelopes can be described as a significant increase in credit card binding, gaining a “marketing model” for hundreds of millions of users at zero cost. Since the process of binding a bank card is quite complicated, most mobile payment apps face a “cold start” problem: how to convince users to sign up for a card? WeChat Red Envelopes cleverly solved this problem. Many users who receive red envelopes will choose to withdraw money, which will naturally trigger bank card binding behavior. Catalyzed by red envelopes, the number of WeChat credit cards has grown exponentially. After the Spring Festival in 2015, WeChat's credit card account successfully broke 100 million, far less than the time it took Alipay to accumulate users of the same size. With the popularity of the innovative form of payment such as red envelopes, WeChat Pay successfully completed a “cold start” and accumulated initial payment users and account funds.

Ride the style of O2O and use the “small amount, high frequency” scenario to cultivate users' payment habits

After completing the initial accumulation of users' credit cards and WeChat wallet funds through red envelopes, how to enrich scenarios and guide users to use funds on the platform has become the key to the next development of WeChat Pay. At that time, it was a stage where the O2O boom was booming. From the second half of 2014 to the second half of 2015, the size of the O2O market grew by more than 50% over half a year. Tencent has led the investment in a series of O2O companies represented by Didi, Dazhong Review, and 58 Home. In addition to financial support, it also complements the WeChat wallet Jiugongge traffic portal and provides WeChat Pay support.

The O2O platform and WeChat have formed a mutually beneficial cooperation model. Under the O2O model, payment is an important step to help close the transaction loop. Without a foundation for payment, innovative models that integrate online and offline, such as ordering meals online and taxis, will not develop so rapidly. At the time, these startups also focused on their main business and had no extra energy to develop their own payment business, so they gladly connected to WeChat Pay. As far as WeChat Pay is concerned, these high-frequency, small-amount payment scenarios have a low entry threshold and high user demand, and are an excellent opportunity to cultivate payment habits and increase user stickiness.

Take Didi taxi as an example: Didi connected to the WeChat Jiugongge portal on January 4, 2014. On that day, when only the iOS version was supported, the number of orders placed through the WeChat portal had reached 20,000, and the number of WeChat payments exceeded 6,000; from January 10 to February 9, WeChat Pay completed a total of 21 million payments, with an average of 700,000 transactions per day. The simple and smooth user experience of WeChat Pay, plus the high subsidies that Tencent invested in at the time to compete with Ali's “quick taxi”, quickly opened a window for users to use WeChat Pay. WeChat Pay also gained great popularity in this ride-hailing war. To this day, Didi Taxi is still the leading WeChat Pay merchant.

This line of thought continues to this day. Although today's O2O market has entered a period of relative maturity and growth is slowing down, finding a new round of high-frequency microfinance scenarios in a period of rapid growth and continuously increasing the penetration of WeChat Pay in all aspects of daily life is still an important means of rapidly increasing the scale of payments. Tencent's investment in companies such as Fresh Pinduoduo and Bike-Sharing Mobike, as well as support at the payment level, all reflect this line of thought.

Make up for the shortage of resources on the operation side through continuous product-side optimization and innovation

Alipay's promotion strength on the operation side is significantly higher than that of WeChat Pay. Inheriting the strong operating genes of “Alibaba”, Alipay often invests sufficient human and material resources in product promotion to attract users with vigorous promotions such as “full reduction” and “rebates.” Take the “Double 12” offline payment 50% discount campaign as an example. A total of 28 million users participated in 2015, and in 2016, with the expansion of the merchant system, more than 100 million users participated. What is behind this national carnival is the huge market investment of Alipay and merchants. Alipay also surpassed WeChat in terms of cooperation with mainstream media such as CCTV.

Unlike Alipay's style, the WeChat Pay operation team has fewer manpower and relatively strict resource investment, and is often less intense than Alipay in terms of operating activities. WeChat Pay is committed to refining products, improving the payment experience, creating innovative payment forms, and accumulating advantages on the product side. This is a consistent characteristic of Tencent: in essence, Tencent is a company where “the product manager decides”.

Actively promote offline QR code payment methods. WeChat introduced the “scan QR code” function before it launched the payment function. At the time, it mainly scanned the code to obtain information. After the launch of WeChat Pay, this function was extended to scan codes to obtain payment information, and applied online thinking to offline scenarios, providing a low threshold, quick and convenient offline solution, which gradually evolved into the standard for offline payments today. The code scanning payment function helped WeChat Pay quickly cover a large number of long-tail merchants: by printing their own QR codes for payment or obtaining official postal QR codes through online applications, these merchants can quickly access WeChat Pay at zero cost.

In contrast, Alipay is much slower to move in the field of offline QR code payments. This is probably because Alipay has already set up a large number of POS machines offline, so there is no need to rely on QR codes to obtain offline access. However, Alipay did not immediately realize that the threshold and cost of code scanning payments are much lower than POS payments, making them more attractive to long-tail merchants. It wasn't until 2017 that Alipay began vigorously promoting “payment codes” for small and medium-sized merchants, slowing down the aggressive trend of WeChat Pay in the field of offline payments.

Using public accounts to provide differentiated services to merchants: The WeChat public account, which was also launched in 2013, also plays an important role in the expansion of WeChat Pay's merchants. With the rise of the WeChat public platform, more and more merchants regard it as an important channel for communication with users, and the demand for the functions it carries continues to grow. WeChat Pay takes the opportunity to provide merchants with functions such as access to payment and customized services, so that users can complete a closed loop of transactions within the public account and assist merchants in the operation and maintenance of public accounts. This was a powerful tool for early merchant development on WeChat Pay. In contrast, although Alipay also has public platforms such as life accounts and applets, its user penetration rate and appeal to merchants falls far short of the WeChat account.

Product-side optimization continues: With the continuous launch of products and functions such as membership card packages and applets, WeChat Pay continues to optimize products based on its own platform features, and is deeply integrated with scenarios to create a smooth user experience. At the same time, Alipay was criticized by many users for developing social features, and ultimately did not become a social app.

WeChat's positioning as an “open and connected” lifestyle platform further empowers payments. Alipay's “wallet” positioning reflects its strong tool attributes — users can only open Alipay with a destination when they have financial needs such as payment and financial management. Although Alipay has always tried to focus on finance and supplement social and entertainment elements, hoping to broaden users' usage habits, the results have not been ideal. However, WeChat, which positions itself as “WeChat is a way of life,” relies on a chain of social relationships and continues to launch modules that meet different needs, gradually evolving into an ecosystem connecting people, hardware, and services. The positioning of the WeChat ecosystem has given more space for the expansion of payment services.

Competition continues: the protracted mobile payment battle between “Alibaba” and “Tencent”

From a strategic point of view, the significance of payment business is to attract a large number of users and capital, and lay the foundation for high value-added businesses such as consumer credit, financial product distribution, and credit reporting. Therefore, Internet giants may not be concerned about the profitability of payments themselves, but rather more concerned about whether payment users can be converted into users of high-profit financial services. Seen from this perspective, although WeChat Pay is ahead of Alipay in terms of the number of transactions, it has yet to completely open up the situation in the critical high-profit business. The battle between the two giants continues, and now the main battleground has already moved to fields such as O2O, new retail, and overseas.

Scenario penetration: from online to offline, offline from retail catering to lifestyle and entertainment, and more scenarios

There is a certain sequence of scenario penetration for electronic payments. Due to differences in the degree of online integration, standardization, and user usage habits of different industries/scenarios, etc., the acceptance threshold for electronic payments is also different. Judging from the development history of mobile payments, the order of development of existing scenarios is as follows:

It first developed mainly for scenarios where life is just needed and where traditional methods of operation are troublesome, such as mobile phone recharge and daily payments.

The second most acceptable category is e-commerce. Because it is a pure online scenario, the threshold for using electronic payments is relatively low. Meanwhile, e-commerce in China, under the leadership of Taobao and Alipay, is also considered the first batch of scenarios where electronic payments are accepted.

Next is O2O, a model of online shopping and offline consumption. Payment is the last step in online activities. Didi Chuxing, Meituan, and Hungry are all typical representatives.

The highest threshold is the pure offline scenario. Because the entire event is carried out offline, it is difficult to bring the separate payment process online, so that people get used to pulling out their phones at the cashier desk to search for QR codes in apps; and unlike online merchants, the number of offline merchants is huge and very scattered, requiring large-scale promotion, which is very time-consuming and labor-intensive. Therefore, offline is the most difficult scenario to enter and the slowest to develop.

At this stage, mobile payments have fully penetrated into the offline scene. In 2017, the mobile payment penetration rate in the online scenario reached about 85%, which is basically saturated; however, the offline market is relatively empty. In recent years, it has become the main battleground for competition among major payment applications. The penetration rate has increased from single digits in 2016 to around 15% in 2017, and there is still a lot of room for improvement. More importantly, the transaction scale of the offline market is huge, about 4 times that of the online market. It will be the main source of future growth in the size of the payment market, and it will also be a must-compete place for giants such as Alipay and WeChat Pay.

Offline is the main battleground for restaurants, supermarkets, and retail, and continues to expand horizontally into fields such as public transportation. The offline market can also be further divided into different vertical sub-industries, and the difficulty of penetrating each sub-industry is relatively different. Currently, mobile payments are mainly expanding in the fields of restaurants, supermarkets, and retail, and are already beginning to see results. However, in fields such as entertainment, transportation, hotels, and healthcare, the penetration rate of mobile payments is not high. All in all, mobile payments are more widely used in the “small amount, high frequency” scenario, while in the “large amount, low frequency” scenario, it still lags behind bank card payments.

Catering: Alipay actively connects with catering merchants through Alibaba's word-of-mouth network, and focuses on penetration in third- and fourth-tier cities. Following the merger and acquisition of “Are You Hungry?” in 2018, Ali fully entered the restaurant O2O field. Tencent is also expanding its catering business by investing in Meituan Dianping. In 2018, the two giants Meituan and Hungry accounted for about 90% of the Chinese restaurant O2O market (based on GMV).

Supermarkets and retail: In addition to actively connecting with merchants, Alibaba and Tencent have also increased investment in leading companies in the industry under the wave of new retail, and have made the integration of payment links an important element. Currently, almost all retailers and supermarkets across the country are on the side of the “Ali Department” or the “Tencent+JD” side. JD, which is allied with Tencent, is also vigorously expanding its own brand specialty stores and convenience stores.

Public transportation: Public transportation is a typical small high-frequency payment scenario. Currently, the average number of daily payments for subways and buses across the country exceeds 200 million, and the average daily amount exceeds 500 million yuan. Payment institutions began to explore in 2015-2016, and began developing in this field in 2017. Take WeChat Pay as an example. Users can activate the relevant city bus code through the “Tencent Ride Code” applet, then swipe the two-digit code to get on the bus at the subway/bus stop, and WeChat will automatically deduct money after completing the trip. There is no need to buy a ticket for the whole process, and there is no need to buy a physical card and the trouble of searching for coins. Currently, it has been connected to nearly 50 cities including Guangzhou, Xiamen, and Xi'an, and is still being further expanded. In addition to regional expansion, gameplay is also constantly being enriched — the bus code piloted WeChat tickets in February 2018: WeChat friends can give away subway tickets, and can also choose personalized ticket designs and add greetings, increasing social and fun.

Alipay's “Empire Strikes Back”: In 2016, Ma Huateng publicly stated that WeChat Pay's share of transactions in the offline market had surpassed Alipay. However, Alipay did not sit idly by — starting in the second half of 2017, it played a series of offline combo punches, including: increasing investment in marketing, strengthening the offline code scanning payment layout, splitting up Reputation into independent applications and directing Alipay with each other, and buying Hungry and deeply integrating it with Word-of-Mouth.

Alipay's counterattack has had some effect: since the fourth quarter of 2017, Alipay and Reputation have been at the top of the iOS free download list for a long time, and even took turns taking first place for a while; in 2018, Alipay's AAU (annual user base) grew by more than 100 million. However, continuous investment in marketing has affected the profits of Ant Financial, the parent company of Alipay: in the 2018-19 fiscal year, Ant Financial changed from profit to loss. Obviously, it is impossible for marketing activities, which are mainly subsidies, to continue uncontrolled over a long period of time. We estimate that in 2019, both Ant Financial and Tencent will be interested in a temporary truce, and the total amount of subsidies for both sides will drop sharply. Next, Alipay will strive to overwhelm WeChat in terms of technology and e-commerce ecosystems, etc., while WeChat will still use its huge social communication volume to stabilize and even increase its market share.

New mobile payment gameplay: gameplay upgrades brought about by technological upgrades and consumption upgrades

Entering 2019, consumers will often see Alipay's “face-brushing machines” in retail scenarios such as supermarkets, restaurants, etc., although few actually “brush their faces.” Over the past few years, the mobile payment user login process has experienced the evolution of password verification, fingerprint verification, and face swipe verification, and will continue to evolve. Alipay and KFC achieved the benchmark application of face-brushing payments as early as 2017 — choose a good meal on the KFC self-service ordering machine, select “Alipay Face Pay”, perform face recognition, then enter the mobile phone number linked to the Alipay account, and then you can pay after confirmation. The payment process takes less than 10 seconds, and there's no need to enter a password or pull out your phone. Unmanned stores, such as Amazon Go, are also leading explorers of cutting-edge technology. Information is captured through technologies such as face recognition and the Internet of Things to make the payment process invisible, and shopping payments can be completed without additional operations.

However, in the field of mobile payments for consumers, technology itself is not a strict barrier — new technology such as face recognition can be used by Alipay and WeChat Pay; it is nothing more than a matter of speed or speed. To establish real barriers, it is necessary to write articles on consumption scenarios and retail formats. In other words, mobile payments are bound to be a piece of the puzzle in the “new retail” landscape, inextricably linked to the new retail layout of the two giants Ali and Tencent.

Alipay: Stronger than operations, the layout of offline scenarios is both early and numerous. Ali began investing in the offline scene in 2014, and pioneered the concept of new retail in 2016, in an attempt to transform the pain points of traditional offline retail with experience and technology accumulated online. “Alibaba” Taobao, Alipay, Gaode Map, Alibaba Cloud, and Reputation Network can form a “closed loop of new retail”, so that users' consumption behavior remains within the system as much as possible. In contrast, Tencent doesn't have a similar closed loop because it doesn't have e-commerce or its own O2O business.

WeChat Pay: The advantage lies in the size of users and innovative products represented by mini-programs. Through sweeping actions, WeChat can naturally connect 900 million online users and offline scenarios; mini-programs focusing on quick and convenient applications are also opening up more and more functions, exploring deep integration with various offline scenarios, opening up users, data, and payment services, and providing a smoother user experience. Users always use WeChat the most frequently and for the most time, which gives Tencent an almost limitless traffic advantage and high diversion efficiency. Here are two typical examples: Starbucks and McDonald's.

Use online traffic and gameplay to promote offline consumption. Take “Talk with Stars”, a collaboration between WeChat Pay and Starbucks, as an example. Users can give each other Starbucks gift cards on WeChat, and users who receive gift cards then go to stores to spend money. This is an example of successfully integrating social elements to promote offline consumption — imitating the interface and operation of red envelopes, users are easy to get started, and can grab coffee coupons in groups, increasing interactivity; the cover and gift content (a certain type of coffee or a certain face value) can be customized, adding interest. These all increase the appeal of gift cards to users.

Open up member information, facilitate users, and empower merchants. Take the McDonald's applet launched by WeChat Pay as an example. When users spend in offline stores, they can order and pay directly online, eliminating the trouble of queuing; at the same time, they can directly earn points. Not only is it convenient for users, but merchants can also obtain first-hand user consumption and credit data, providing a foundation for accurate services and marketing in the future. Alipay's “Life Account” and applet also have similar functions.