Source: Zhitong Finance and Economics

Author: Li Junyi

The turmoil in the global economy and markets this year is largely due to a growing recognition of the seriousness of US inflation and the Fed's determination to fight inflation, Zhitong Financial APP has learned. It is understood that when the Fed began to raise interest rates in March, the market expected the terminal interest rate to be only 2.8%. Now, as of mid-November, that expectation has risen to 5%. So will the Fed's terminal interest rates continue to rise? This article will discuss in detail the circumstances under which the Fed will raise the terminal interest rate to 6%.

When the natural unemployment rate is underestimated, the terminal interest rate may rise to 6%.

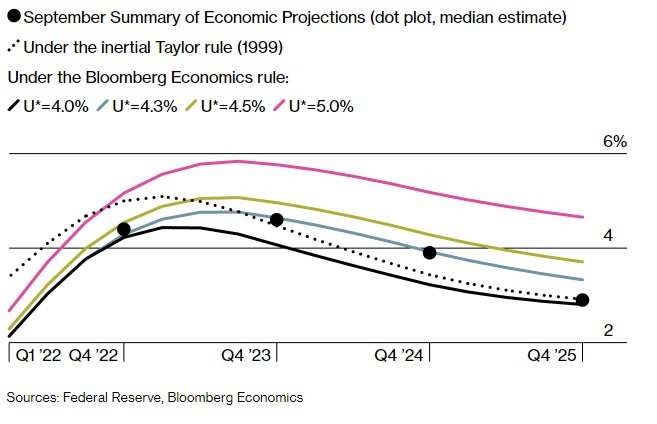

In the September interest rate resolution, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) dot chart showed that the trajectory of raising interest rates was rising despite the deteriorating growth outlook in the US economy. A simple explanation for this anomaly is that the committee's estimate of u* has risen from the traditional 4%. It is reported that u * is also known as natural unemployment rate (NAIRU), that is, the unemployment rate related to price stability.

In the September interest rate resolution, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) dot chart showed that the trajectory of raising interest rates was rising despite the deteriorating growth outlook in the US economy. A simple explanation for this anomaly is that the committee's estimate of u* has risen from the traditional 4%. It is reported that u * is also known as natural unemployment rate (NAIRU), that is, the unemployment rate related to price stability.

The u * value that best matches the September dot chart is 4.4% in 2022, 4.3% in 2023 and 2024, and 4.0% in 2025. This shows that FOMC believes that the current u * is temporarily high and is expected to gradually fall back to the normal level before the epidemic by 2025.

图1

But what if it goes higher instead of falling back to u *? Fed officials estimate it to be between 5% and 6%. This is perfectly reasonable given the pain and chaos in the labour market caused by the COVID-19 epidemic, and Federal Reserve Chairman Powell himself has said that the natural unemployment rate has "risen significantly". So, while keeping FOMC inflation expectations unchanged, a 5 per cent u* estimate means a terminal interest rate of 6 per cent.

Slower productivity may also push up the natural unemployment rate

It is understood that broader macroeconomic factors such as slower productivity growth could also push u.s. higher.

Workers usually demand higher wages to compensate for higher inflation, but if the wage increases demanded by workers exceed the income companies receive from their output, the result is higher unemployment. At the same time, high inflation means a sharp change in relative prices. Under the assumption that input costs are stable, enterprises that want to optimize production processes may find their old methods outdated or inefficient. This is what happened in the 1970s, when productivity growth was lower than wage growth.

In addition, on the balance sheet, companies charge themselves fees for property, machinery and other capital stocks based on lease prices. High inflation has raised rental prices and discouraged investment. Coupled with the uncertainty of inflation and central bank interest rates, as well as geopolitical factors, add additional obstacles to costly long-term investment.

All these factors that weighed on productivity growth in the 1970s also exist today, suggesting that potential economic growth is continuing to slow from its already low rate before the COVID-19 epidemic.

To measure the impact of the economic slowdown, what will happen if total factor productivity growth between 2022 and 2025 is 0.5 per cent lower than currently expected, according to FRB/US, the main model of the US economy? This is equivalent to a slowdown in US gross domestic product (GDP) from the current 1.8 per cent to 1.3 per cent by 2025.

Lower potential growth rates will mean more overheating and higher inflation. Assuming the Fed recognises this and responds appropriately, FRB/US data show that the federal funds rate will be above the current baseline of the FOMC and remain high for longer. Calculations show that the Fed's projected terminal interest rate will rise to 5% in 2023, much higher than the 4.6% shown in the bitmap in the minutes of the Fed's September meeting.

Prolonged market turmoil or persuading the Fed to stop raising interest rates

In addition, there is a view that the market overestimates the risk that the recession will keep the Fed on hold. Powell is understood to have learned the lessons of the 1970s, when the Fed suspended the rate hike cycle prematurely, with disastrous results, even though inflation remained uncomfortably high to support economic growth. Based on this view, some analysts expect the Fed to leave the final interest rate unchanged at 5% during the US economic downturn in the second half of 2023.

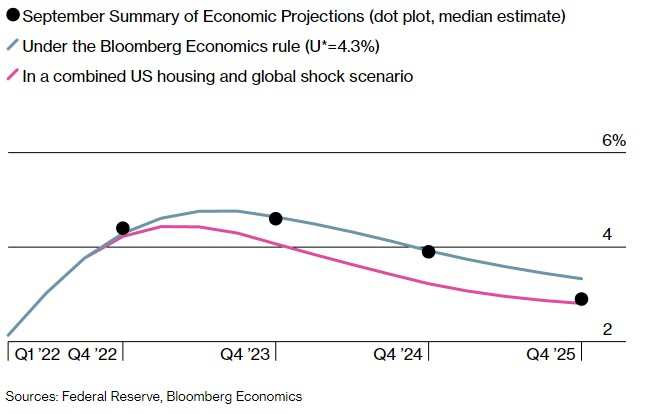

But in spite of this, it is not difficult for the market to spot the major risks that are coming, from the collapse in US house prices and the spillover effects of turmoil in the UK market to the looming recession in Europe. In addition, the Fed has repeatedly indicated that it is willing to suspend interest rate hikes if the data support it. During the European debt crisis in 2013, for example, the Fed delayed tightening because of turmoil abroad, so it could happen again.

In addition, through the shake simulation of the internal model of the US economy, it can be seen that the US has been doubly hit by weak global demand and increased financial turmoil, resulting in a surge in the volatility Index (VIX), widening credit spreads, a stronger dollar and reduced exports. If that happens, weaker demand will reduce inflation, and the Fed may tighten slightly less than currently expected, with the federal funds rate at 4.1 per cent instead of 4.6 per cent in 2023.

图2

It is worth mentioning that Fed officials recently rarely agreed on the need to raise the federal funds rate to the level shown in the dot chart. However, analysts and market participants are increasingly criticizing that the Fed's preferred path is too high. Another view is that the FOMC's forecasts for the federal funds rate are by no means too tough, and that various labour market characteristics suggest there is still more room for upside.

Summary

If the Fed underestimates the natural unemployment rate (u *), or if the epidemic leads to a significant deterioration in productivity, the Fed may raise the terminal interest rate to 6%. On the other hand, if the market is hit more than so far, and this long-term market turmoil may be enough to persuade the Fed to stop at lower interest rates.

Edit / somer

在9月份的利率决议上,美国联邦公开市场委员会(FOMC)的点状图显示,尽管美国经济增长前景恶化,但加息轨迹仍在上升。对这种反常现象的一个简单解释是,该委员会对u*的估计从传统的4%上升了。据悉,u*也被称为自然失业率(NAIRU),即与物价稳定相关的失业率。

在9月份的利率决议上,美国联邦公开市场委员会(FOMC)的点状图显示,尽管美国经济增长前景恶化,但加息轨迹仍在上升。对这种反常现象的一个简单解释是,该委员会对u*的估计从传统的4%上升了。据悉,u*也被称为自然失业率(NAIRU),即与物价稳定相关的失业率。