Before the whip of inflation is over, the whip of raising interest rates is coming again. Raising interest rates will dampen consumption through three major transmission channels, including borrowing costs, wealth and income.

Oil prices took a short break before the Memorial Day weekend, but the average oil price hit an all-time high again in the first week of June as summer travel demand approached.

Consumers are exhausted from 40 years of record levels of inflation.

But the whip of inflation is not over, and the whip of raising interest rates may be coming again soon.

What is the impact of rapid interest rate hikes on consumption?

Under the sandwiched attack of inflation and interest rate hikes, can US consumption still hold up?

Consumer confidence is declining, is consumption really so strong?

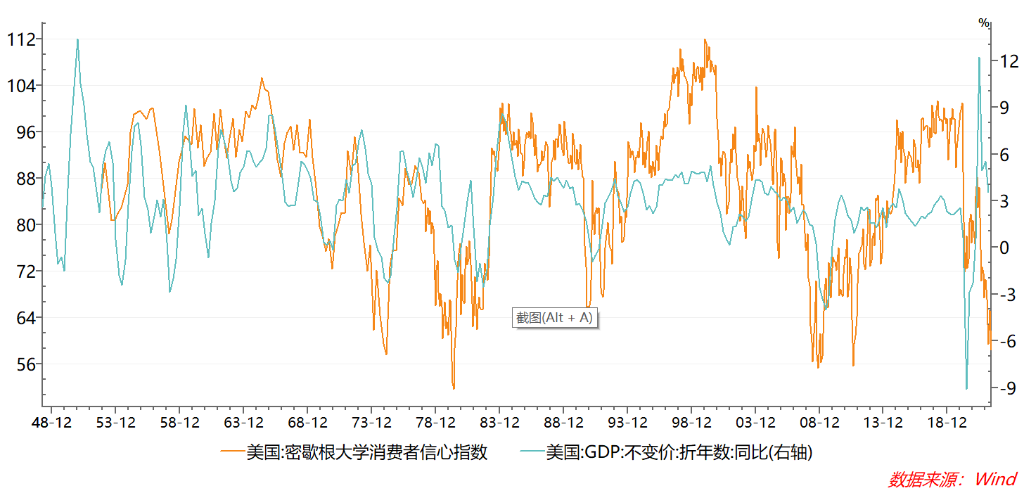

Over the past 60 years, private consumption has gradually accounted for 70 per cent of US GDP. Private consumption is highly correlated with the annual change in GDP. There has never been a decline in private consumption, but a rise in GDP. Given the huge role of private consumption in the economy, a drop in consumer confidence below 80 is a six-month to one-year lead for a recession.

Recently, hit by inflation, Michigan's consumer confidence has fallen below the readings of the recessions of 1991 and 2001, second only to the stagflation of the 1970s and the financial crisis of 2008.

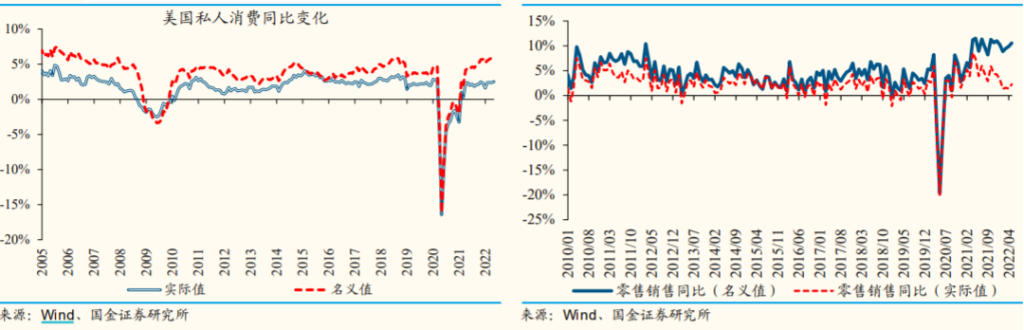

In terms of nominal consumer spending and retail sales, the figures are still very strong. The compound growth rate of US private consumption rose to 6 per cent in April, well above the average of 3.9 per cent over the past decade. At the same time, the compound growth rate of retail sales rose to 10.6%, which is also much higher than the average level of the past 10 years.

But if you factor out the price, the actual level of US consumption is far less strong.

According to research by Guojin Securities, excluding price factors, the compound growth rate of real consumption in the United States in April was 2.5%, slightly higher than the average level of 2.2% in the 10 years before the epidemic. The actual growth rate of retail sales was only 2.3% over the same period last year, also slightly higher than the average level in the 10 years before the epidemic.

In the hot consumption of durable goods, contrary to the nominal growth rate, the real compound growth rate of retail sales of major durable goods such as home appliances, furniture, cars, and building materials all dropped sharply, at 30%, 28%, 8% and 5% of the historical percentile, respectively.

Actual service consumption is even weaker, with a real compound growth rate of only 0.9%. In particular, the compound consumption of non-essential services such as transportation and entertainment, which is repeatedly restricted by the epidemic, is still in a negative range compared with the same period last year.

So, after determining that consumer sentiment and real consumption are falling, our question is how inflation and interest rate increases are affecting or will affect consumers' purchasing power.

Inflation squeezes consumption

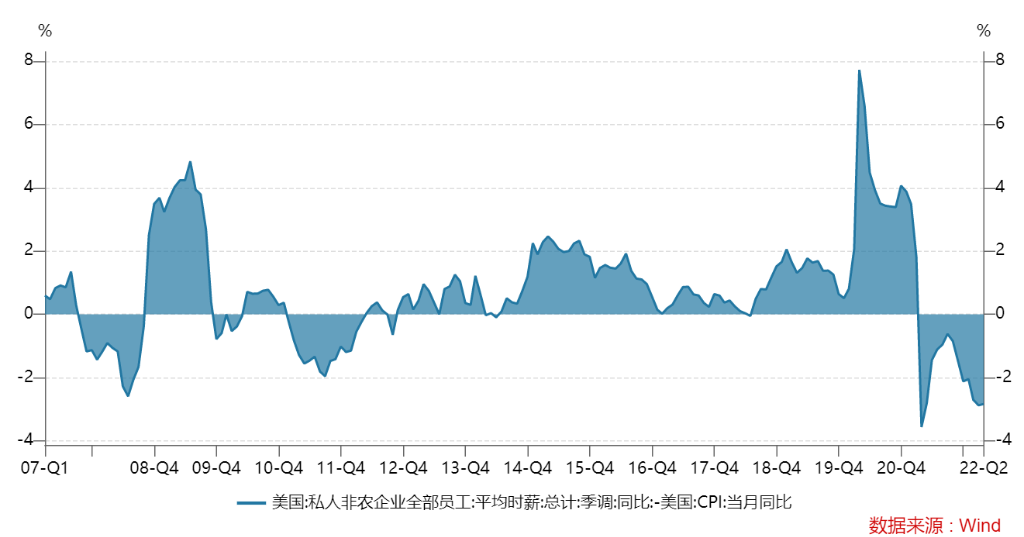

First of all, the most direct impact of inflation on purchasing power is the decline in real income.

If the income of consumers keeps pace with or exceeds the rate of inflation, inflation does not necessarily weaken purchasing power. But the truth is that real income (adjusted for inflation) has fallen for more than a year. In other words, although nominal wages are increasing, their purchasing power is declining.

With inflation growing at 8 per cent and wages rising by about 5 per cent, consumers are actually "cutting wages", whether they realize it or not. The situation is even worse for the lower and middle classes, not only because they have a higher marginal propensity to consume, but also because the prices of food, energy and rent, which spend most of their income, are rising faster than the overall rate of inflation.

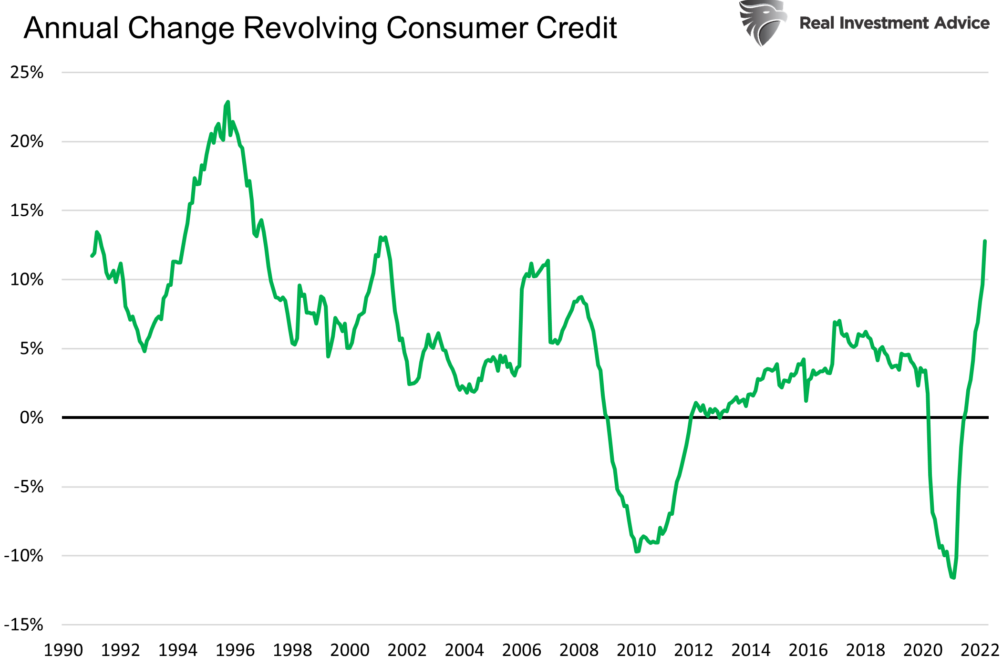

Second, inflation will consume savings and increase debt to curb future consumption.

In order to maintain a certain amount of purchasing power, consumers will use their savings. Although the absolute value of personal savings is still high, the level of personal savings adjusted for inflation has actually fallen to its lowest level in eight years. Consuming savings to support consumption means less spending or an increase in debt in the future.

Similarly, consumers have increased their use of revolving consumer credit instruments such as credit cards. The year-on-year growth rate of consumer credit card debt has climbed to its highest level in more than a decade. Consumers can continue to borrow, but higher credit card interest rates and larger debt balances will limit consumers' future use, thereby curbing future consumer spending.

The whip of raising interest rates is coming.

In the face of 40 years of high inflation, at a time when consumers are already exhausted, the Fed will eventually have to raise interest rates quickly to calm prices. But keeping prices down (or at least steady) is good news for consumption? It's not.

Tighter monetary policy will curb consumption through three major transmission channels, including borrowing costs, wealth and income. Similarly, austerity will also lead to increased income and consumption inequality, masking the huge impact on middle-and low-income people.

A. borrowing costs-when the Fed raises interest rates, the cost of new borrowing increases, dampening demand in interest-sensitive sectors of the economy, namely durable goods and housing. The average cost of taking on existing debt is also rising, but lower-income households are more likely to use credit cards and convert variable-interest-rate debt, so they are more vulnerable to interest rate risk.

One of the main channels of monetary tightening affecting consumption in the short term is the borrowing cost of floating interest rates. The interest rate increase will immediately be passed on to the interest rate charged by banks on revolving consumer credit, mainly credit cards. As a result, households that rely more on revolving credit (credit cards, etc.) will clearly feel the rise in costs, thereby reducing their spending on interest-sensitive projects. The categories of expenditure funded by consumers with revolving credit mainly include "high-priced" durable goods, such as household goods and electrical appliances. Therefore, the consumption of these items is very sensitive to interest rates. The American Chamber of Commerce's consumer confidence report in May showed a decline in willingness to buy homes, cars and major household appliances.

In terms of outstanding debt (mainly mortgages accounting for 70%), it has less impact on consumption because it is now relatively insensitive to changes in the federal funds rate. Because more than 99 per cent of outstanding institutional MBS and most household debt (90 per cent) are held at relatively fixed interest rates.

Before the housing bubble burst in 2007, the proportion of MBS held by outstanding institutions at adjustable interest rates peaked at 12 per cent. Today it is less than 1 per cent. Mortgage debt is more vulnerable to interest rate risk, which leads to the global financial crisis. It shows that current consumers have reduced their interest rate exposure.

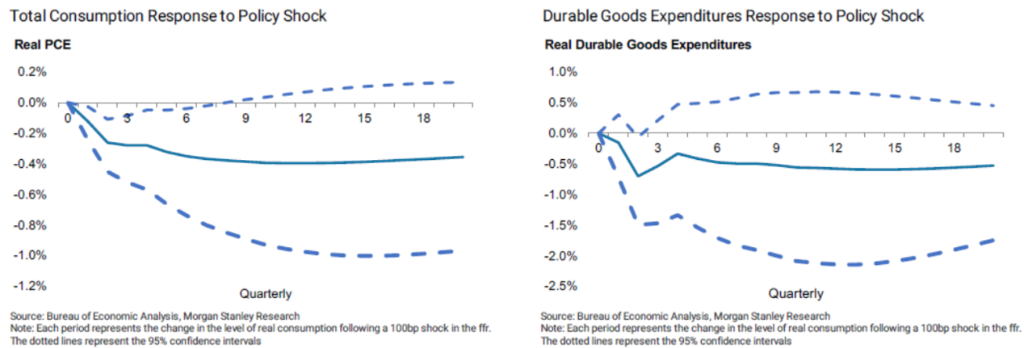

According to Morgan Stanley's consumer response model to interest rate hikes, the impact of a 1 per cent one-off interest rate hike would lead to a net drop of 0.3 per cent in real PCE levels in one year and 0.4 per cent in two years. Most of the decline is reflected in spending on durable goods. Spending on durable goods fell by 0.7 per cent in the two years after the policy shock and 0.5 per cent in five years. But the response to services and non-durable goods was much less. The decline in durable goods was 2.7 times that of non-durable goods and 7.8 times that of the service sector.

At the same time, Morgan Stanley cited studies by Johnson and Li (Federal Reserve,2007) and Baker (2014) to point out that the distribution of costs raised by monetary tightening through credit channels is unequal. The spending of low-income households in the face of income shocks is likely to be hit even harder because they must maintain a greater proportion of consumption and leverage.

B, wealth effect-higher interest rates affect the valuation of financial and non-financial assets, which in turn affects consumption through wealth channels. Higher interest rates should directly reduce financial wealth through falls in bond and other asset prices. In non-financial wealth, higher interest rates increase the cost of buying a house, which may hurt the value of the house.

Morgan Stanley's model shows that because 70 per cent of financial assets are concentrated on the balance sheets of the top 20 per cent of households, and the transfer of the wealth of high earners to consumption affected by higher interest rates is negligible, therefore, the overall response of wealth channels after interest rate increases is relatively small. But it has a more significant impact on the bottom 60% of income distribution.

Non-financial wealth (real estate) is more responsive to policy shocks than financial wealth. Compared with financial wealth, non-financial wealth holds more evenly in the whole income distribution, so the transmission of consumption through non-financial wealth effect may be greater than financial wealth effect.

Taking home purchase as an example, Morgan Stanley said that real estate assets began to decline more significantly in the fourth quarter after the policy shock. In other words, raising interest rates has a lagging impact on housing transaction volume and housing value.

Higher interest rates will dampen new mortgage lending, which in turn will dampen home sales. But in the months after the rate hike, rapidly rising mortgage rates tend to be accompanied by higher sales of existing homes as potential buyers see their last chance to lock in low interest rates. It wasn't until about six months after interest rates rose sharply that home sales peaked and then tended to fall. This has been reflected in May when the number of home listings in the United States increased for the first time in 19 years and the total number of mortgage applications fell to a 22-year low.

Because the bottom 60 per cent have a greater decline in wealth and their higher marginal propensity to consume (MPC). The model shows that five years after the shock of raising interest rates by 100 basis points, the implicit impact of consumption in the bottom 20 per cent is that real personal consumption expenditure fell by 0.26 per cent, while real personal consumption expenditure in the top 20 per cent fell by only 0.04 per cent. The consumption of low-income families through wealth channels has been hit harder.

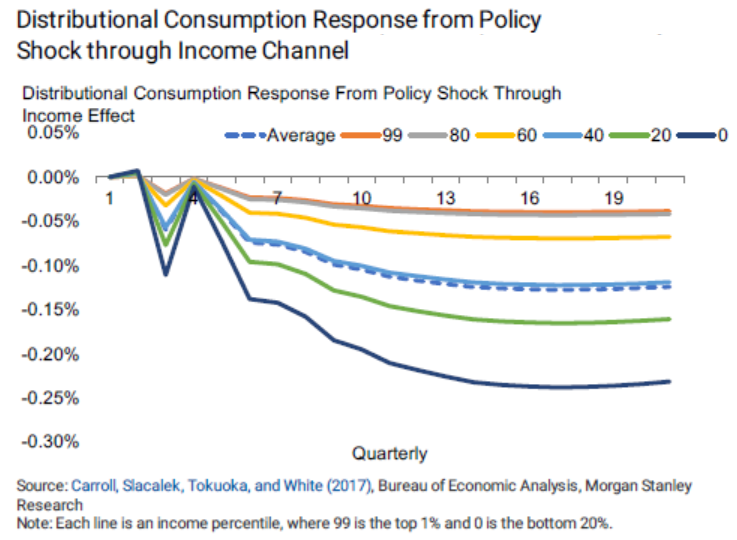

C, income effect-high interest rates slow down the economy and reduce the demand for labor, which in turn reduces labor income. The decline in labor income will eventually reduce consumption. Morgan Stanley also pointed out that the decline in income and consumption is not consistent, and households also at the bottom of income distribution show a stronger consumption response.

Monetary tightening will lead to a decline in disposable income, but the impact will be delayed, less than the immediate decline in consumption caused by changes in borrowing costs. The model shows that the decline in income in the five quarters after the impact of austerity will have a more meaningful impact on consumption. Real disposable income fell 0.1 per cent in the first year and 0.3 per cent in two years, while consumption fell 0.3 per cent and 0.4 per cent respectively. The decline in consumption is greater than that in income.

Similarly, in the income effect, monetary tightening will have a greater impact on the households at the bottom of income distribution. The reason is that disposable income has fallen the most, savings buffers are low, and government transfer payments will fall even more after contractionary currency shocks.

The model shows that three years after the shock of raising interest rates by 100 basis points, the impact of consumption of people under 20% is that real personal consumption expenditure fell by 0.24%, while the real personal consumption expenditure of the top 20% fell by only 0.04%.

With the strong consumption of durable goods or near the end of the line, whether there can be a significant boost in service consumption in the future will be the key to testing the quality of US consumption. Lingering inflation and tightening on the path of rapid interest rate hikes have gradually put consumers in trouble.

The decline in consumer confidence does not mean that the economy must decline, but after all, 70% of the economy is closely related to the fate of consumers.

Edit / irisz